GROSS/45 1954 - Rear Window - Hitchcock in the grid

In London or in New York, it's always location location location

Gross is every year’s top-grossing movie, since 1913, reviewed.

REAR WINDOW, Director ALFRED HITCHCOCK. Cast JAMES STEWART, GRACE KELLY, WENDELL COREY, THELMA RITTER, RAYMOND BURR. Production company PARAMOUNT PICTURES. 1954. Running time 111 MINUTES

“Rear Window is set on a fictitious 125 West 9th Street, nonexistent because West 9th has a career of only a single block.” - Peter Conrad, Art of the City

I feel like an idiot. I swerved what is probably the actual top-grossing movie of 1954 -White Christmas - and went for one that probably isn’t but is definitely one of the most important works in the canon. So now I’ve got to write about it. And obviously I’m reluctant to make you plough through another review of this particular work of art, this Brunelleschi’s dome of a movie. A movie from the very peak of its creator’s career, from the moment of his greatest facility. So this is basically fragments…

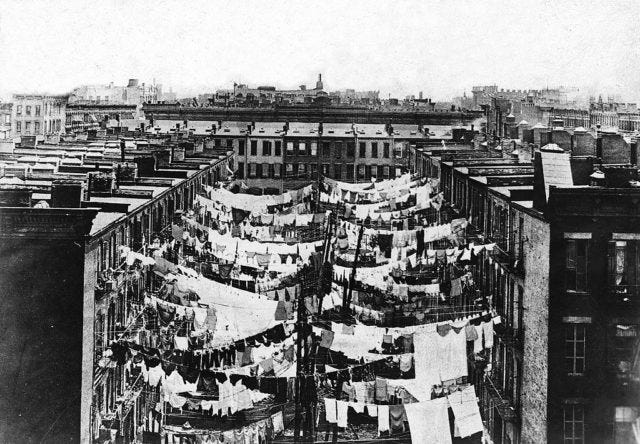

Rear Window is an apartment romance: location and architecture are vital: the city grid and the accommodation slotted into it - for working people and for the bourgeoisie. We’re in New York in the 1950s - America’s factory, the capital of labour. Almost a decade after the war there are still hundreds of thousands of manufacturing jobs in Manhattan alone, tens of thousands of factories in the city. Many of the New York’s expansive 18th- and 19th-Century residences have been carved up into apartments to meet the demand. Labour is stacked basement to attic-room in all but the poshest neighbourhoods of New York.

Hitchcock’s set, built on the enormous Paramount lot in Los Angeles, is based on a real New York courtyard. But what Hitchcock built wasn’t quite a duplicate of its West Village model - he’s added some variety. So what we get is a kind of apartment sampler - accommodation of half a dozen different types - railroad apartments, studios with huge picture windows, one-room flats, family apartments, garden flats… all jammed into a kind of haphazard grid - like the city’s, but tipped up to vertical for us so that we can get a good look at the inhabitants.

From this grid Hitchcock allows his variegated humanity to spill out into view, brightly lit, as if in a display case. But when it comes to that most private of domestic activities - the murder and dismemberment of a resented spouse - the lights go out, the curtains are drawn. If you have nothing to hide…

We’re in Jane Jacobs’ neighbourhood. The urbanist lived for twenty years on Hudson Street. She lead the movement of ordinary New Yorkers that killed off Robert Moses’ plan for a freeway that would have cut right through the Village - although she’d have been 20 blocks North of the new highway (she wrote The Death and Life of Great American Cities here too).

Megalomaniac Moses hated Jacobs - for New York’s urban planning czar she was the ultimate NIMBY, imposing her cutesy, bourgeois version of city life on ever-changing, ultra-capitalist New York, regardless of the demands of money or even of working people. But for her, Greenwich Village was urban perfection. Doors that opened directly onto the street, social mixing, a varied streetscene.

Jacobs’ bottom-up urbanism was not radical - she promoted a classical liberal idea of the city as the ideal market - a benign, self-organising network. The title of her other famous city book paraphrases Adam Smith.

But she has influenced… well, everyone. From cuddly Marxist sociologist Marshall Berman to King Charles to conservative neo-traditionalists tearing down brutalist landmarks everywhere. The Rear Window courtyard - and the busy street we can just make out through the alley on the left - are Jacobs’ ideal - except for the murderer, obviously.

Our self-important photojournalist hero, L.B. "Jeff" Jefferies (James Stewart), lives in a two-room apartment - his observation post - in a neighbourhood that, by the 1950s, has been accommodating artists and poets and freaks of various kinds for decades. Marcel Duchamp, Maya Deren, Philip Guston and Anaïs Nin were all living in the Village in this exact period. Charlie Parker died there the year after the film came out.

Jeff’s not hip or transgressive or even an artist (his best-known photo is of a crash at a car race). And it’s obvious he’s from the comfortable outer suburbs. He likes the vibe of the Village - thinks it says something about his liberal, freewheeling nature - and he believes that moving uptown with Lisa would be death.

Lisa (Grace Kelly) is more of a Park Avenue type. Jeff’s girlfriend works in fashion and shows up to Jeff’s confinement (he’s broken his leg and must suffer seven weeks in plaster) in a different couture outfit daily (styled by Edith Head, obvs). We are dazzled. She’s slumming it and the appreciable class tension is critical to our enjoyment.

You’ll pick your side: middle-class Jeff’s irritating, sanctimonious pride in his job - one of the most pretentious and indulged professions in the whole culture - grants him a feeling of superiority over his shallow, upper-class girlfriend.

Lisa is self-aware, though, and can see the vast chip on Jeff’s shoulder but she loves him anyway. Working-class nurse Stella (Thelma Ritter), who visits daily, complicates the class geometry. It’s an insoluble three-body problem. The best scenes involve the three of them.

We probably have to consider Alfred Hitchcock’s childhood, across the Atlantic in the capital of capital. Until he left home he knew only apartments (we still call them flats over here). His shopkeeper dad moved the family from one London flat to another, always the very particular kind that you find above the shop. In Leytonstone it was a greengrocer’s. Little Alfred knew the feeling of enclosure, the steep stairs down to the street, the forced proximity that apartment-dwellers lived with.

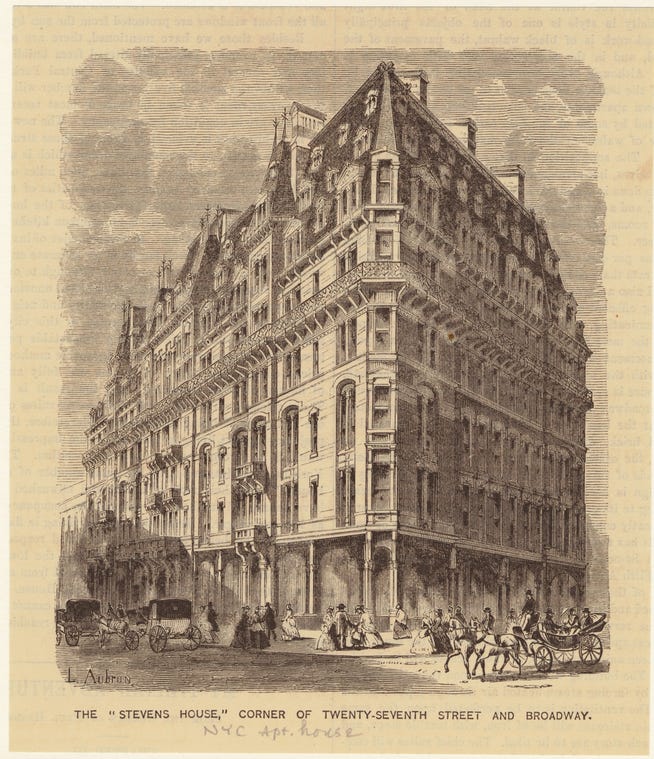

Of course, it’s this kind of claustrophobic intimacy with one’s neighbours that those free-ranging non-conformists were getting away from when they escaped England for the frontier in the first place - freedom expressed in spatial terms - so there wasn’t much enthusiasm for apartment living in the republic until late in the 19th Century, when the first ‘French flats’ started to go up in growing cities around the USA - New York first, of course.

It was the rich who were first invited to adopt this European urban form. Big, purpose-built blocks - Beaux Arts slabs and towers like the Dakota and the Stevens House - offered modern amenities not unlike those provided in the billionaire pencil towers of today. Dining rooms and dumb waiters, laundry services, games rooms. These pre-Great Depression apartment blocks were full-service.

Flats went down market as the century proceeded and urbanisation intensified. There was a convergence of the tenements built for workers and the twenty-room aerial palaces built for the rich. New laws mandated bathrooms and kitchens be added even to small flats. Rent controls were introduced. The modern apartment was born.

Margaret Thatcher, born a generation after Hitchcock, would have felt some connection. She spent her early years above her father’s grocer’s shop in the Lincolnshire market town of Grantham. She was a Methodist, though, and, although we think Hitchcock’s faith helps to explain his twitchy, self-flagellating art, Thatcher’s Methodism definitely doesn’t.

Methodists had been liberals and reformers for two hundred years and, by the time Thatcher was born, the House of Commons was already filling up with a new generation of working class Labour Methodists. Not Margaret’s style, though - she infiltrated the Conservative Party, an Anglican fortress, instead.

In London, The Peabody Trust, a philanthropic charity founded by millionaire American banker George Peabody, had begun building housing for ‘the working poor’ in the 1860s. By the 1950s, there were tens of thousands of Peabody flats. They were carefully pitched just one level above the slums that still disfigured the city.

My parents were granted a Peabody flat when they married in 1957 - one room with shared bathrooms and kitchens on alternate landings. They loved it. It was a clean and properly-maintained escape from the grim lodgings they’d have had to take up without it. My dad, in particular, became a Peabody superfan and would rave about the man and his mission. He owned biographies and histories of the buildings.

Alfred Hitchcock, the petit-bourgeois Londoner, was a cut above the working poor but he’d have ridden the tram past various Peabody model dwellings on his way to and from school and work. I feel sure that the two Peabodys in his movies must have been in some way inspired by that name and its presence in the London of his childhood.

Hitchcock’s first (never completed and now lost) Gainsborough picture was actually called Mrs Peabody (also Number 13) and, in his final work, a Rashomon-style courtroom episode of the Alfred Hitchcock Hour, George Peabody is the only reliable witness.

In the year Rear Window was released Hollywood made over 50 Westerns. Most of these movies literally invert the tortured spatial dynamic of Rear Window, pushing Westward, claiming space by the acre, by the square mile.

Is Rear Window really the biggest film of 1954? Well, possibly not. The other list I reference for this purpose says it’s White Christmas. So sue me.

Is my slight but unarguable resentment of Hitchcock’s easy brilliance and the completeness of this thing a reasonable critical premise? Could I build an analysis of this movie on the basis of irritation at how effortlessly brilliant it is? I suppose not.

Kenneth Goldsmith’s Capital: New York, Capital of the 20th Century is an eccentric effort to bring Walter Benjamin’s Arcades Project to the Big Apple.

It was Harold Wilson, Labour Prime Minister, who said that British socialism owed more to Methodism than to Marxism.

Wikipedia says that Hitchcock had an essentially photographic memory for London bus and tram numbers and would say them out loud when he saw them on clapperboards in later life. He included buses in so many of his movies it’s hard to count them. The time-bomb sequence in Sabotage is a work of art. The fact that both of my parents were bus conductors while they were living in Peabody’s is of no relevance whatsover. Hold very tight please.