Gross is every year’s top-grossing movie, since 1913, reviewed.

GOING MY WAY, LEO MCCAREY, PARAMOUNT PICTURES, 1944, 126 MINUTES. BING CROSBY, BARRY FITZGERALD, RISË STEVENS

(listen, you Americans are just going to have to put up with me typing ‘labour’ throughout this newsletter. I’m sorry but there’s nothing I can do about it. It’s something to do with the Treaty of Versailles or the Thirty Years War or something).

New York in 1944 is not yet the capital city of capital (that’s still London) but is definitely the capital city of American labour. The city is packed from end to end with factories big and small. On Manhattan island alone there are 500,000 manufacturing jobs. In the city there are 40,000 factories. Streets that, decades later, will become shopping destinations or hip restaurant clusters are lined with workshops and warehouses. All those famous block-wide downtown lofts are factories, filled with workers and stacked to the eighth and ninth and fifteenth floors. And New York labour is organised too. Unions, even in small and now forgotten industries, are active and militant.

Employers are tough too, workplaces are raw and dangerous. Across the 20th Century strikes have been put down with violence or lock-outs or worse. The war has brought unity, though. Industrial action has almost stopped, but it’s brought working people together too and given them a sense of their power and the potential to improve their lives. As war ends labour feels its strength. The strike wave of 1945 and 1946 has its own Wikipedia page.

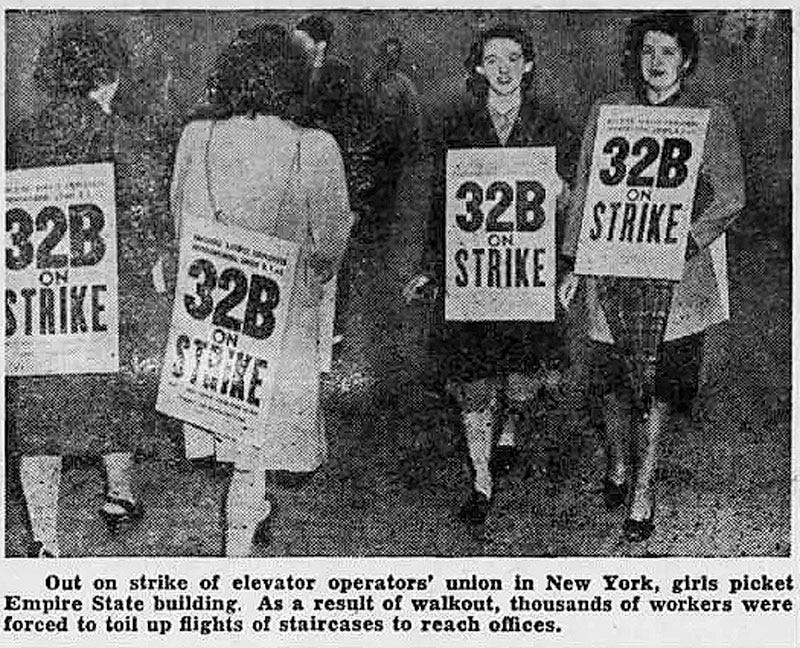

Weeks before the war ended 15,000 New York elevator operators and doormen went on strike - in high-rise new York an enormously effective action. Over a million workers had to stay at home. In the same year New York newspaper and mail deliverers went on strike. Mayor La Guardia was furious and responded by reading out the funnies on his weekly radio show. At this time the port of New York was responsible for a third of US trade. When the tugboat crews walked out in 1946 the city became hysterical, fearing oil and coal shortages which didn’t materialise - the strike was settled. It didn’t always go the workers’ way but often enough for a sense of the potential of organisation to arise. The golden age of union power had begun.

So, in New York in the 1940s, labour is everywhere - the cacophony of production can be heard on almost every street corner. Only the most prosperous neighbourhoods are quiet - and even in the quiet parts of town, every brownstone and mansion is busy with domestic staff. In New York there’s poverty, overcrowding and indigence but there’s also work, lots of it. In the war industries especially but also in the growing market for consumer goods that would define the post-war boom.

Life is about work but the movies are about money

There’s work in Going My Way. I mean workers are present. But they’re not working. Here, in 1944’s biggest film, set in working class New York City, it’s as if the labour has been deleted. Removed for fear it’ll cause some kind of revolt.

I keep saying this (I need a new theme). I said it last time too. A lot of the American movies I’ve been watching here celebrate capitalism. But I guess that’s a pretty dumb statement. I mean what else would these big-money Hollywood productions from big-money oligarch-run Hollywood studios celebrate?

But what I’m trying to get at is the intensity, the sheer overwhelming ideological oomph of the Hollywood project in this period. It’s hard not to conclude that the Hollywood system has set itself up in opposition to the expansion of worker power and worker confidence, against the big, abstract ideas - emancipation, autonomy, fulfilment - that characterised the first Hollywood period. Profoundly, also, of course, against the particular model of emancipation offered by the Soviet Union and its satellites.

American movies - and especially the American movies of this critical mid-century period - are responsible to a large degree for the hold capital has over our imaginations and our sense of ourselves practically everywhere. If they don’t advance the virtues of capitalism itself - and a lot of them do, in the most direct way possible - then these Hollywood pictures will sanctify the market, the individual, private property, the merits of hard work, the entrepreneur, the free-trader, the investor, the landlord, the smallholder. Watching these films in sequence - and watching the hits, the ones that made a lot of money - is very clarifying about how we wound up in America’s thrall, in the American orbit.

Hard-edged and hard-hearted

There are some exceptions on this list. Artists like Charlie Chaplin, Rex Ingram, James Whale, D.W. Griffith (Griffith is promoting something older and nastier than capitalism, of course). But it’s also evident from the sequence, starting in 1913, that, as the form matures, its ideology is hardening. The dreamy, other-worldy charm of the silent cinema has been replaced by the hard-edged characters and scenarios of golden age Hollywood. Graft, cruelty, sacrifice, deception, betrayal, murder. Silent actors couldn’t get work in the talkies because of their thick European accents or their difficulty telegraphing emotion without mugging - but as often they failed because they were too soft-focus or too poetic.

The thirties and forties is the second Hollywood, the Hollywood of the self-possessed hero wearing something sharp or tailored. Bette Davis, Clark Gable, Barbara Stanwyck, Spencer Tracey: simply not possible in the first Hollywood, the Hollywood of poetry, soulful lovers, fairy stories and uncomplicated laffs.

Show me the money

It’s honestly no wonder we’re all so defeated, those of us who live in the orbit. We’ve been so thoroughly acculturated by the Hollywood machine - the ultimate capitalist tool. We can’t imagine another story-world beyond it. These movies, the Hollywood hall of fame, are an instrument of capitalist realism.

We soak up film after film in which the hero is an archetype of striving or independence or, simply, uncountable wealth. We meet outsider-entrepreneurs, triumphant criminal masterminds, plutocrats without restraint, ingenious chancers, mafiosi, wannabes, con-men, grafters and small-businessmen. But also the people they crush and demean - losers, shirkers, tramps, hobos, bums, the defeated.

In my dream

This is why I keep finding myself returning to the other option, the road not taken - my fragile cinema counter-example. The movie-making tradition that - in my dream, in a parallel universe - might have won, might have taken over, shaped the history of cinema, given us a different model, made us different people. The beautiful, humanist, pro-worker French movies of the thirties (the Popular Front movies and the films of the ‘poetic realists’), the creations of men and women who had lived through the beginning of Europe’s great crisis (and would live through more too).

And why I keep trying to find parallels between the American films and the French ones of the period. This movie, for instance, has many resemblances to a Renoir or a Carné film. Poor kids, multiple Catholic priests, a nasty landlord, city streets and shabby neigbourhoods, a policeman in a rain-cape. But those French movies, they invariably celebrate the worker, the peasant, sometimes the patient shopkeeper or the decent headmaster - not the owner or the lender or the rentier. When we meet aristocrats they are fallen or humanised by suffering - or they’re fighting for the same cause as the workers in their fields or factories and there is love between them.

This is not a complaint

Going My Way is a beautiful and humane film, and funny. You’ll cry. Bing Crosby does that thing that makes you want to put your head on his shoulder. Barry Fitzgerald as Father Fitzgibbon, the superannuated priest whose church is about to be repossessed, is a pathetic-comic gem. Actual opera singer Risë Stevens literally never stops smiling benignly, like the patron-saint of smiling benignly (by the end, you’ll be smiling benignly too). The choir of reformed urchins and hoodlums is the perfect vehicle for redemption - from poverty but also from wickedness. In 1944, with the war at its grim peak, this must have been a cathartic treat. And there are songs too, crooned, mainly, as you’d expect, by Crosby, including several that became big hits.

So we’re in an unspecified Irish neighbourhood of New York. The Irish are everywhere. And this is the period of New York’s absolute dominance. At the end of the second world war, New York is to America what America is to the world. There’s sparkling wealth here - the plutocrats own the famous streets of midtown Manhattan - but this is uncomplicatedly a working class city. The priests in Going My Way are missionaries sent to a proletarian land. And they’re Irish too. The Irish dominated the American Catholic church in this period and the trans-Atlantic pipeline of priests and seminarians was busy.

Going My Way is not just a hymn to capital; it is, remarkably, a hymn to debt. Our wicked landlord (Gene Lockhart), who, at the beginning at least, really is a villain from a melodrama, holds a mortgage over St. Dominic's Church, and it’s in arrears so he plans to foreclose on the old priest, have him chucked out and his church demolished for housing. He won’t even buy the old man a new boiler because what would be the point? The place is coming down anyway.

Bing Crosby’s Father Chuck O'Malley is despatched on a rescue mission by the Bishop to sort out the parish’s finances. He has to do this delicately because the old priest has been told only that he’s getting a new assistant. O’Malley is one of those Hollywood Catholic priests you’ll be familiar with. He’s a worldly man, breezy, personable - and a singer. We learn that, before he took holy orders, he was a bit of a lad and might conceivably have played the field a bit. Now he plays golf. I’ve met a few priests and this type definitely exists. You’ll find them at the bar after the funeral.

The landlord’s redemption, as you’d expect, sees him abandon his plan to pull the place down and come around to the priest’s side. His son (James Brown), once an apprentice villain, enlists in the army and, before he’s shipped off, finds the love of an honest woman (Jean Heather), although she is poor (she’s also Lola, tragically unloved in Double Indemnity, from the same year). Their love saves the landlord, who can no longer find it in him to harass the priest.

When the church burns down the reformed landlord raises money for a new one (although we’ve actually been wondering if he burnt it down) and then, as the ending begins to resolve, we learn that he has gone further and guaranteed the church’s future. And he’s done this by, er, providing another mortgage. Only in an American movie can the assumption of debt constitute an unqualified happy ending. Music swells, credits roll.

Going My Way is on Apple TV+. There’s a Blu-Ray.

Researching this one I can across an amazing 1944 election film, directed by Chuck Jones. I wrote about it last week.

I think the reason there are so many of these worldly priests in the movies is the difficulty of casting a gorgeous, moody or funny A-list actor and then asking him to give us humble or pious. Not possible. At the very best we get brooding and sweetly self-deprecating. But see Gary Cooper in 1941's Sergeant York if you’re looking for Christ-like.

The elevator operators’ strike triggered, predictably enough, a big and effective effort to automate them out of existence. Where they survived it was purely for ornament in fancy buildings.

The only truly wicked character in the film, the only one not offered redemption, is the grumpy man Father O’Malley encounters when playing softball with some kids in the street at the beginning. A big hit from one of the boys smashes the man’s front window. A tetchy exchange with the Priest follows and our man carefully informs us he is an atheist. Say no more. I could easily write another post about religion, morality and orthodoxy in Going My Way.

Some of the numbers in this edition are from this excellent review of Working-Class New York: Life and Labor Since World War II by Joshua Freeman.