GROSS/17 1927 - maudlin, cruel and mother-fixated

The Jazz Singer is a sentimental melodrama about ethnicity, assimilation and the miserable realities of capitalism.

Gross is every year’s top-grossing movie, since 1913, reviewed.

THE JAZZ SINGER, ALAN CROSLAND, WARNER BROS/VITAPHONE, 1927, 96 MINUTES.

A festival of uncoordinated movement

Al Jolson is no actor. He’s more of a vibrator. He quivers, bouncing from scene to scene as if powered by a tightly-wound spring, his rubber face stretched by something that’s supposed to be emotion. It’s not convincing. He’s not much of a dancer either. And my extended investigation of dancing in the silent era tells me he’s no outlier. No one could dance before sound, before Busby Berkeley really. It’s embarrassing. If you google ‘why is the dancing so bad in silent films?’ you’ll learn nothing but I guess we can conclude that dance makes no sense without synchronised music.

It was sound that triggered the accelerated evolution of movie dancing. Suddenly timing was no longer optional, tightly synchronised movement replaced slack vaudeville shuffling. Dancers quickly became athletes and specialists, flighty chorus lines disciplined platoons. Choreographers arrived on the lot. But here, in a movie that’s still mostly silent, Jolson - who called himself ‘the world’s greatest entertainer’ - jiggles his wiry torso and snakes his hips distressingly. His scarecrow arms move independently, as if not connected. The crowd goes wild. You might want to look away.

An ethnic melodrama

The reason you never see The Jazz Singer on the TV is the blackface scenes in the final reel, now considered unpalatable. In one scene Jolson performs ‘Blue Skies’, already in make-up, and it’s awkward to watch. In another, though, we see him in his dressing room, artfully applying his blackface make-up and pulling on a ‘negro’ wig before going out to sing ‘Mother of Mine, I Still Have You’ (only the first of two truly awful mother-fixated hits from this film). The casual focus on the process and Jolson’s practiced ease with the burnt cork makes the scene more than awkward. It’s a kind of torture to watch - Jim Crow as entertainment.

This film is not incidentally about race. It’s at base an ethnic melodrama, about the tension between the old country and the new; the immigrant and his assimilating offspring, the host culture and the alien. And it’s all discussed in the frank way that’s only possible in a country of immigrants. Al Jolson plays Jakie Rabinowitz, son of the principal cantor at a Lower East Side synagogue in New York. He can sing so it’s assumed he’ll follow the old man into the trade. But as a kid, Jakie has already secretly swapped the sacred for the profane and is singing the sentimental hits of the day in local bars, shuffling his hob-nail boots in the sawdust and rattling a cup for pennies. Soon Jakie’s left his devout and inflexible father and his devoted mother and is making a life for himself as an entertainer under his new name Jackie Robin.

The blackface element and the Jewish element collide here. The minstrel shows, in which white artists performed a formulaic programme of songs, slapstick and sentimental drama parodying the black arts and black culture, had more or less disappeared by the time The Jazz Singer gave them this unexpected boost. Blackface had a complicated meaning for Jewish artists like Jolson. Because the minstrel shows had been, for decades one of the most important forms of entertainment for white audiences in the USA, they had a central place in popular culture that only the movies themselves would finally eclipse. Entry to this world meant a lot to an immigrant.

For Jewish entertainers, very often fresh off the boat and scrabbling for status and a living in the teeth of overt and unapologetic antisemitism, putting on blackface and singing the old songs was the most profound kind of assimilation - an acceptance into the heart of white American culture. The power of blackface for these European Jews was that it could momentarily delete the problematic otherness of their origins. A Jewish performer was never more American than while wearing blackface.

There’s a scene where Jack, in his dressing room, ready to go on, looks in the mirror and his own face, in blackface, is replaced by a cloudy vision of his father the cantor singing for his congregation. It’s a headspinning moment - a kaleidoscopic restatement of the paradox of American ethnicity in this moment. The blackface performer in the mirror is American in an unqualified way, the devout jews at prayer are not.

There is no alternative

The structure of the film is pretty familiar. In act one, the immigrant son abandons the faith and the stultifying traditions of his parents and moves into the forbidden world of secular entertainment, anglicising his name, working hard and becoming a star. In act two, the immigrant returns to his family, earnestly willing himself back into the heart of the community he left behind. It doesn’t go well. In act three, there’s a reconciliation.

But here’s the nub of the movie. It’s not the reconciliation you’re expecting. As a child Jack abandons his family and his faith for show business and when he finally returns, on the brink of stardom, he’s asked to choose again: fame or family.

Jack’s attempt to reconnect with his family permits an argument about show business vs religion but also - and more profoundly - about money vs family, capital vs community. Once the tension is set up we learn that Jack’s much-anticipated Broadway premiere - his name enormous on the marquee - is going to clash with his obligation to sing in the synagogue, standing in for his dying dad. The film’s leading characters lay out the choices. Should Jack honour his family and his heritage and skip his opening night to sing in Shul? Or should he honour his contract with the theatre and his adoring audience and dump the congregation?

And let’s be clear, in a present-day movie a disagreement like this could be resolved in only one way - in favour of family and community. No Hollywood studio could do otherwise now. Family, heritage, community, work-life-balance, the sacred duty to ‘be there’ for your kids - in every case will now trump work, even the mighty work of the headlining entertainer. What does workaholic Scrooge proxy Walter (James Caan) in Elf do when offered the choice of working late Christmas Eve to satisfy his tyrannical boss or reconnecting with his son and saving Christmas? Obviously the latter. What is John McClane’s real quest in all three Die Hard movies? To get back to his family and to hell with stupid police chiefs and feds. There are a thousand examples from the contemporary cinema and no exceptions (find one, leave a comment!).

All American films are about capitalism: change my mind

But The Jazz Singer dates from the era before family became a sacred trust for Hollywood. Also, in economic terms, from long before the catastrophe of the mid-century, the second world war and the boom that followed it, before the Keynsian settlement and the social contract and the long period of improving wages that came with it - a Chevy in every driveway, a job for life, an apple pie cooling on the window sill. Before the first baby boomer walked the earth.

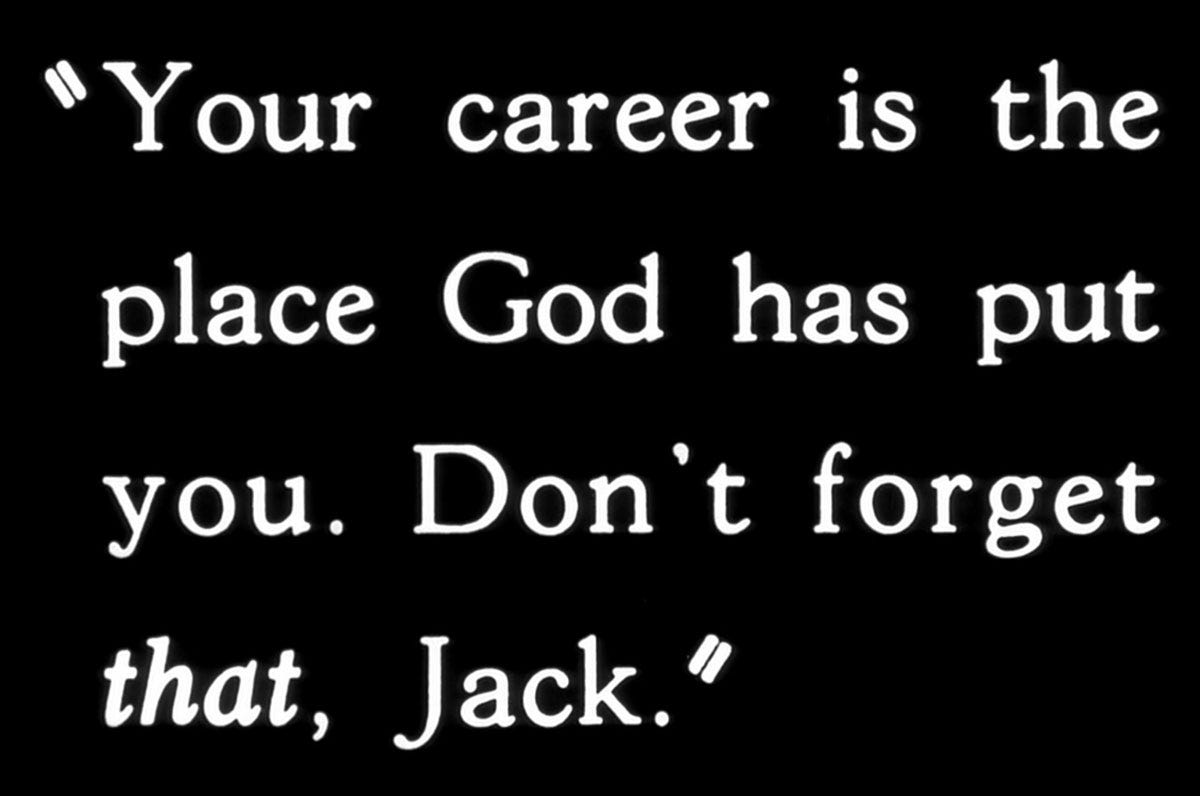

This is the raw capitalism of the first half of the 20th Century - of the United States, the soon-to-be titan of the world economy, about to displace all the old economies as they succumb to war and degradation. This unmediated, unmodulated capitalism is more than an ideology in The Jazz Singer. It’s an unarguable fact of life, unchallenged by anyone in the movie. Jack’s early admirer and showbiz sponsor Mary Dale, a famous dancer who falls for his schtick early when she sees him step up to perform in a nightcub, struggles to make sense of the call of family and faith: “I think I understand Jack - but no matter how strong the call, this is your life.” When his resolve weakens as the Day of Atonement approaches, she drives it home:

Jack has no way out. Even Sara, his mother, the custodian of all that is warm and familial, sees the inevitability of Jack’s new calling: "here he belongs. If God wanted him in His house, He would have kept him there. He's not my boy anymore—he belongs to the whole world now." Show business has won. And here show business is, of course, a shallow proxy for capitalism, for the totalising, secular creed of America - Jack could have been an insurance salesman or a truck driver. He happens to be an entertainer.

Even Jack’s last-minute decision to skip his big Broadway opening night and sing the Yom Kippur Kol Nidre at his father’s synagogue is oddly compromised. As he begins to sing and his father hears his exultant tones from his deathbed across the courtyard and dies happy, it’s not a noble acknowledgement of duty - it’s a surrender to the old world and the old ways. Jack does his duty and it’s moving enough but his redemption doesn’t come here, before his father’s devoted congregation. It comes afterwards, when Jack returns to his true vocation, in the theatre, before his devoted congregation.

The Jazz Singer’s coda, an arbitrary postscript added to the theatrical version to harden the movie’s American edge, is the performance that you’ll know, if you know anything at all about this film. It’s another teeth-grindingly sentimental hymn to mothers - ‘My Mammy’, a song that would have been quickly forgotten if it weren’t for this performance. Present in the audience is Jack’s contented mother, now reconciled to his new calling and to his final joyful assimilation to the American way of living.

The version of the movie that’s on Amazon Prime is 96 minutes long and seven minutes of that are given over to an extended overture and to a long passage of ‘exit music’, presumably meant to showcase the film’s sparkling Vitaphone sound.

I learnt a lot about the complicated ethnic dynamic of 1920s American show business from this LRB review of Michael Rogin’s book about blackface in the movies.

See 1928’s Lights of New York for another example of 1920s hyper-capitalism.

Here's a list of all the top-grossing films since 1913 and here's my Letterboxd list.

And here’s another top-grossing list.

You write so well, and the films allow for such great writing.