GROSS/16 1928 - broken windows, broken promises and broken hearts in the Big Apple

Am I overdoing it here? I've written 1,000 words about a shabby, second-rate film.

Gross is every year’s top-grossing movie, since 1913, reviewed.

LIGHTS OF NEW YORK, BRYAN FOY, WARNER BROS., 1928, 57 MINUTES.

Lights of New York is in almost every respect a bad film. A 56-minute nothing, an over-extended short subject, a low-grade B-feature with a plodding pace. Dialogue is ponderous, staging is mechanical, story is weak.

But, it’s the very first, feature-length, beginning-to-end talkie. And, in this, it’s remarkably confident. The cast is full of pros, with decades of movie experience between them. The female lead Helene Costello is, amazingly, a second-generation film star, already almost 20 years into her career. Voices are authentic and well-rendered - there’s an obvious understanding of how voice can reveal character. And there’s technical ingenuity. In this famous scene, Wheeler Oakman as 'Hawk' Miller, speaks into a microphone disguised as a telephone, advancing the plot with an impeccably sinister line: “…take him for… a ride.” Intriguingly, actors speak slowly throughout - is Foy making an assumption about his audience’s ability to comprehend speech after all those years watching the action and reading the cards?

What’s fascinating about this awful film is not the competent, first-time sound, though. It’s the uncanny sense of a genre arriving fully-formed, of the whole history of gangsters, goons, saps, enforcers, nightclub toughs, wise-guys and dames - how they speak as well as how they move - initiated right here.

Original gangster

So much of the final form of the gangster talkie is present in New York Nights. The language is hard-boiled: guns are ‘rods’, squealers are ‘dirty rats’, corpses are ‘stiffs’. Actors employ accents that hover between Cagney and Pesce - a kind of whiny, parody NYC that’s almost Damon Runyon. You’ll recognise the tone from every subsequent tri-state gangster film.

It’s always fascinating to try to trace the origin of the narrative forms that shape these early films. But it’s tricky here. With Westerns we’ve got half a century of cowboy novels and Wild West Shows; melodrama is a thread all the way through literature; the early comedies carry forward vaudeville essentially intact. But where does the gangster form come from? Had the cast been honing these back-alley voices in the theatre? Was the scriptwriter consciously deploying the new hardboiled argot? It’s a puzzle - the cast of this film is essentially 100% cinema-trained - barely a year of theatre between them. Radio drama hardly exists. How did they acquire these polished, low-life vocal characterisations?

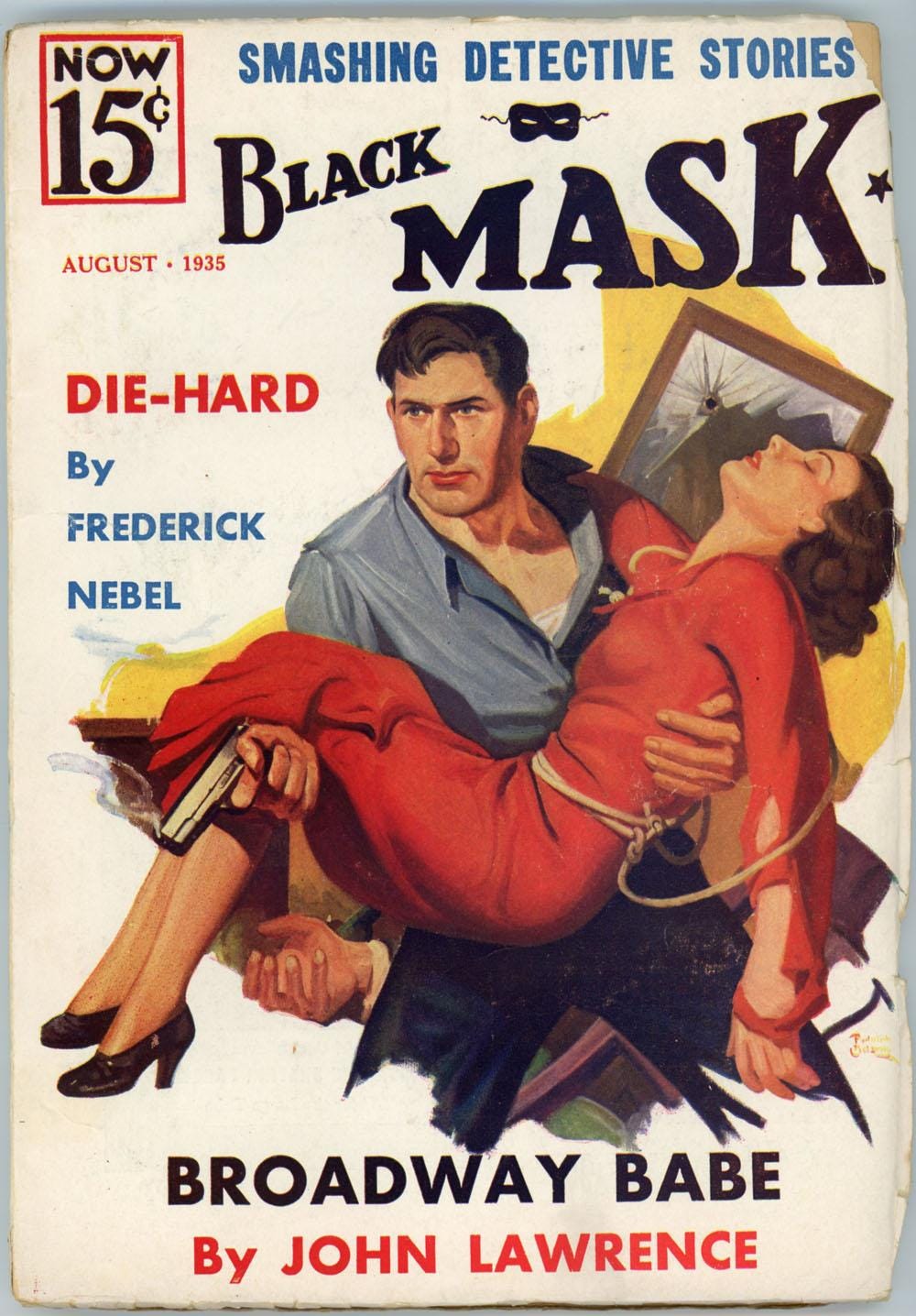

H.L. Mencken’s Black Mask Magazine had been prototyping what we now know as hardboiled for a few years before this film was made but Sam Spade, Marlowe and the Continental Op were still almost a decade away - film noir even further. There had been crims on the big screen for years, of course, but no one had ever heard them speak. Poe and James and Conan-Doyle gave us the detective but not the gang-lord and the bag-man and the moll. We have to conclude that there’s real narrative innovation here - that Foy and his writers (one of whom was comedian Hugh Herbert) are inventing the form right before our eyes (and ears).

The settings are fully mob-drama-compliant too - a failing upstate hotel, a barbershop in the roaring forties that’s a front for a speakeasy, the nightclub behind it and the owner’s upstairs office where he hides the liquor in a room behind a false bookcase. We could be in Scarface or the Sopranos.

And there’s an enjoyable if slightly awkward comedy mood here - the pair of junior bootleggers who lure our hero to New York have a hapless, Laurel and Hardy vibe and scenes are assembled as if for a comedy pay-off. When our hero and his sidekick try to conceal a dead bootlegger by hauling his corpse into the barber’s chair and soaping him up for a shave it’s pure Chaplin.

Capitalism unconstrained

I don’t want to overinterpret this really pretty insubstantial movie but this proto-Goodfellas, like every work of art, has a political and social context - and we’re conscious, right from the beginning, that it’s strikingly different from the context that produced the most famous movies in the genre - Godfather, Scarface et al fifty and sixty years later. The late twenties was a different period all together.

And what characterises this story, what is evident from the very first big-city scene, is an uncomfortable mood of uncontained menace, of a story that’s taking place in a harsh and unforgiving place in a country that hasn’t acquired all of its modern, mediating institutions yet - all the machinery of a state that promises us protection from arbitrary violence and exploitation. We’re palpably in a transitional America - between the explosive, no-rules expansionary phase and the less dynamic consolidation period that we now know is coming to an end. This is the era of capitalism without constraints, a robber baron America, a gangster America.

Nobody knew it, of course, but the roaring twenties were about to come to a nasty end with the Crash and the subsequent immiserating depression and we’re still decades from the long period of moderation and post-war prosperity1 that produced all the sophisticated mob masterpieces of the seventies and eighties (and the happy crew of bien pensant liberal arts majors and film-school grads2 needed to bring the criminal underworld to life in these movies).

The city in Lights of New York is made of cardboard but it’s authentically tough and it’s plausible to say that this is because the moderating institutions of the later liberal state have simply not arrived yet. Everything is raw. We encounter the ‘Federal Men’ who police prohibition and the old-school city cops who pursue the murderer of our bootlegger but there’s no greater sense of a sheltering state here than there is in the Westerns of the period. You’re on your own, people.

1920s New York is not a state of nature but it’s a frontier town. The film’s critique is not the later liberal one of ‘society’ or of the conditions that produce crime and violence but much more crudely of the outlaw and his wickedness. It’s a comicbook morality tale. In this it has more in common with the superhero movies of more recent decades - good vs evil played out in a contextless moral void - than with the psychologically complex gangster narratives of the intervening decades. There are no psychotherapists here and no diagnosis is offered.

But every character in Lights of New York is in some way vulnerable - to brutalisation by an unaccountable bootlegger or to arbitrary police action, to murder by a scared and abused wife, or just to ever-present unemployment and destitution. They live lives closer to the cruelty and precarity of Dickens’ London or Hugo’s Paris. Men are possessive or predatory, women defeated and threatened - our hero Eddie uncaringly insists that his girlfriend Kitty (top-billed Helene Costello) continues to dance at the speakeasy despite the obvious threats to her safety and routine harassment from her handsy boss - they need the money to escape to a better life (he gives her a gun - “if anybody annoys you, well you just fire it in the air a couple of times and that’ll scare them away.”). She accepts her fate. This city cannot protect her.

I watched the film on Daily Motion, which is a first for GROSS. It’s cropped on the left-hand side as an effect of the sound aperture, which is something I just learnt about.

The film’s sound was originally recorded on a Warner Brothers Vitaphone disc, not an optical strip on the projected film. A 16” disc, turning at 33⅓ rpm, was mechanically synced to the projector. The quality was great but as movie sound improved Vitaphone faded.

Two or three musical numbers - with the obligatory flat-footed dancing (what is it with the terrible dancing in these twenties movies?) - suggest the primary imaginative outlet for the sound pioneers. It’s a proto-musical.

We’re also about 50 years - in the other direction - from the wave of novels and stories of the emerging money metropolis - Henry James and Edgar Allan Poe and Horatio Alger and Stephen Crane and all those 19th Century Eastern seaboard aesthetes charmed by the glamour of the new American metropolis and willing into being a civilised, ordered city of rules.

Here's a list of all the top-grossing films since 1913 and here's my Letterboxd list.

And here’s another top-grossing list.

Notice I have not used the word ‘neoliberalism’ once in this review. You’re welcome.

Coppola graduated in Theatre Arts at Hofstra, Scorsese’s MFA is from NYU, De Palma’s M.A. in Theatre from Sarah Lawrence College. David Simon edited the college paper at the University of Maryland. There are no outsiders in the gangster storytelling elite.

I always appreciate those who can make sense of moviemaking. Might be a dumb question here from a non-industry enthusiast. What do you think is the hidden aspect few know about scriptwriting, Steve?