GROSS/12 1924 - orientalism, swashbuckling, love and brutality at sea

The Sea Hawk is a surprising round-trip from Cornwall to the orient and back - faith, race, law, economics, sex and sword-fights - it's all here.

Gross is every year’s top-grossing movie, since 1913, reviewed.

THE SEA HAWK, FRANK LLOYD, FRANK LLOYD PRODUCTIONS, 1924, 123 MINUTES, U.S GROSS $2,000,000.

In case you’ve forgotten, you’re travelling with me through the whole history of the movies, stopping at the top-grossing film from every year. We started in 1913 with an organised crime morality-tale called Traffic in Souls. We’re up to 1924 and an authentic maritime adventure with a complicated orientalist subtext and some comedy. Tell your friends this week’s film is The Sea Hawk!

Finally, an opportunity to keep it short. Succinct. Pithy even.

The Sea Hawk, according to this list 1924’s biggest movie (grossing $2M in the USA), doesn’t really warrant a lengthy review. I mean it’s a lot of fun - authentic swashbuckling with some sweet comedy moments. I could, I suppose, tackle it from various angles that would produce something longer:

As a major production: it’s genuinely vast. There are sea battles and hugely-elaborate sets - in Tudor England and in a slightly out-of-focus Algeria and on various boats - and a handful of the biggest stars of the era.

As an orientalist text: it’s packed with sexy Eastern fantasy, fabulous if slightly generic Islamic decor, beastly Moors lusting over milky-skinned European maidens etc.

Or I could go to town on the wildly Freudian storyline - so many warring brothers and fathers and daughters and converts and enslaved beauties and homoerotic bonds made in suffering and oiled bodies whipped in the sun and… Sorry.

Or I could just read it as historical fiction. There are many splendid and sometimes unintentionally comic elements. The Elizabethan setting sometimes collapses into the vaguely pre-modern and sometimes becomes weirdly Victorian.

It might also be fun to watch The Sea Hawk as a naval epic. The ships - for which the amazing Fred Gabourie is credited - are excellent and cleverly based on various existing boats, plausibly dressed as Spanish argosies and Moorish galleys and terrifying 20-gun English warships (towed around the locations by a helpful U.S. Navy warship I learn).

But no. I’m going to do The Sea Hawk in five gifs instead.

How to enjoy a knighthood

No question, if I’m ever knighted this is how I’ll enjoy it. With very visible satisfaction, smoking a pipe with one leg over the arm of my huge baronial chair and two beautiful dogs from some kind of noble, hunting breed on hand. This shot sets the film up: Tressilian is an honoured veteran of the wars with Spain and he’s basically retired. But his quiet life is about to be disrupted dramatically…

In her splendid autobiography Gloria Swanson says that Milton Sills, our knight, was a sweet and painfully shy man when off screen and that he could hardly be separated from his own pipe. Of course Kenneth Anger says he committed suicide by driving his car off a cliff in 1930 but it seems that he literally made that up and Sills actually died from a heart attack at home in 1930.

Elastic, you say…

What’s going on here? Claire Du Brey, billed only as ‘Siren’, gives us another of those looks that seems to explain the Hays Code all on its own. We learn from an intertitle that the Cornish siren’s conscience is ‘elastic’ and that her husband is old. Is she a prostitute? Or just a party animal? I honestly can’t tell, but she’s surrounded at an afternoon affair in her lovely garden by lusty young men competing for her attenton. It’s a very pre-code moment. Ladies of easy virtue of this kind disappeared almost entirely once the code was in place - at least ladies who were not apparently tormented and later punished for their naughtiness. In the Sea Hawk this not-very-matronly matron stands in immediate contrast to heroine Lady Rosamund Godolphin, played by Enid Bennett, whose purity and naivety run like a kind of irritating thread through the whole two hours.

“I toiled at the oar of a galley until it formed my body into steel and robbed me of a soul”

The plot moves quickly. Sir Oliver, once his quiet retirement is disrupted, finds himself a galley slave on a Spanish vessel overseen by brutal and imperious nobles. At the oars he meets a ‘high-caste Moor’ called Yusuf-Ben-Moktar, played by Albert Prisco (actually a Neopolitan) and they become fast friends. Oliver is so mistreated by his Catholic overlords that he converts to Islam on the spot - “a curse on those that call themselves Christians and countenance such cruelty.” Oliver’s ascent in the Muslim pirate hierarchy is fast - he is soon a feared buccaneer and takes the name Sakr-el-Bahr (the Sea Hawk, obvs).

The galley slave business obviously seems implausible. I mean they knew about sails, right? But in fact warships of every nation were powered by brutalised men pulling on long oars until well into the 18th Century (although towards the end they were mostly deployed for prestige or as a display of military power).

The truth of this thankless profession is that most of those who rowed the warships of the era were not actually enslaved men but convicts or prisoners-of-war (sometimes even paid staff). The French powered their Mediterranean fleet with convicts until the mid-18th Century - they were branded with ‘GAL’ and - thanks to a decree from Louis XIV - served at least ten years at the oar. In the French criminal justice system all convicts came to be known as ‘galériens’. Victor Hugo’s Jean Valjean wore the brand.

“Two hundred philips for the milk-faced girl”

A nasty turn of events sees the Sea Hawk’s delicate - and slightly dim - love-interest Rosamund put up for sale alongside other European captives at an auction in Algiers. The dynamic range of the Kodak celluloid used in the twenties puts Enid Bennett’s skin at exactly the white point - she’s the palest thing in the picture. And she is, of course, titilatingly déshabillé in time for her appearance on the auction block - a bidding war ensues.

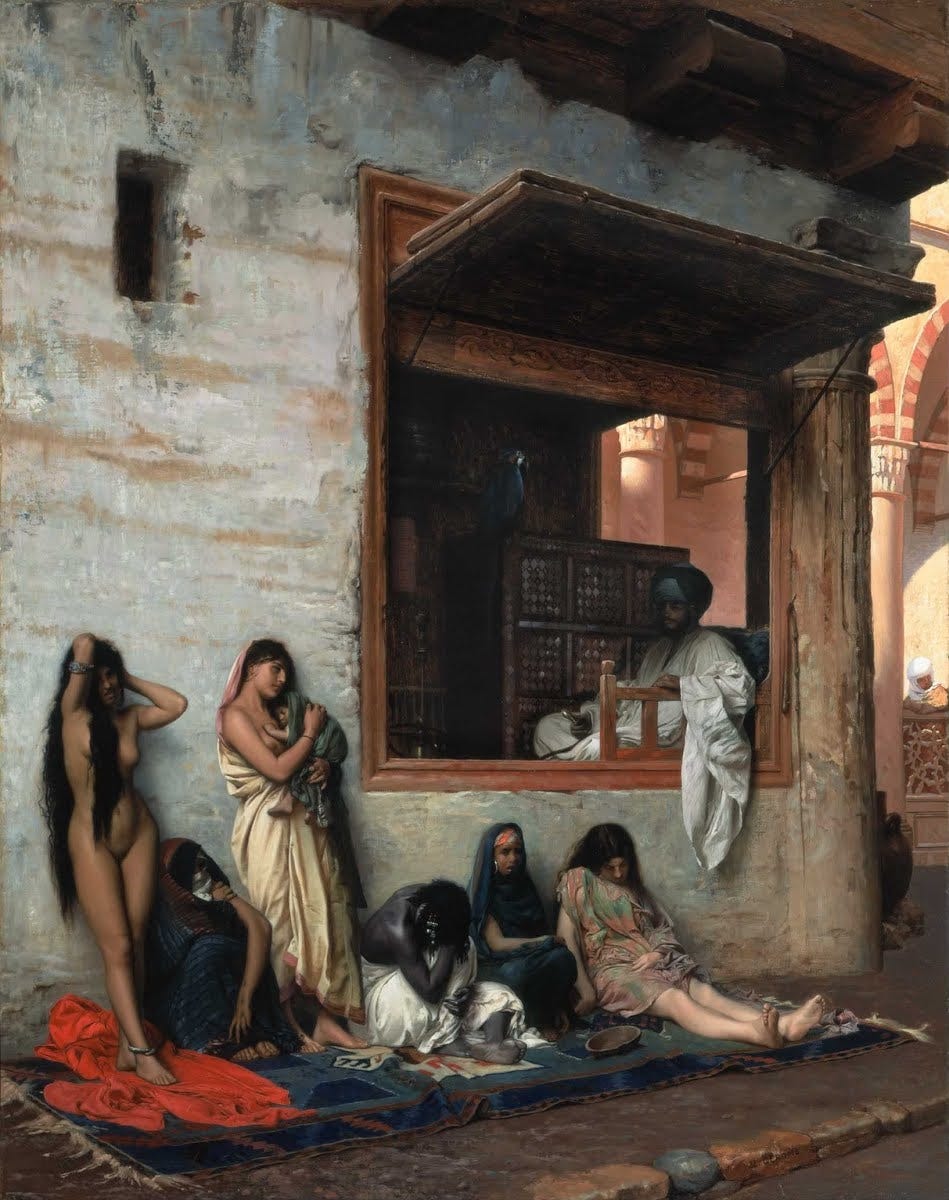

Slave markets and harems had been producing colourful fantasies like this for European elites for over a hundred years. The most important painters of their era, especially in France, were churning out what we would definitely now classify as soft porn for discrimating 19th Century collectors. Gérôme, Ingres, David and Delacroix - the hyper-productive, high-end neoclassicists - all participated. These guys - and countless secondary artists - painted female nudes in a way that would have been impossible (and much less lucrative) in conventional subject matter (the trigger, by the way, for this explosion of nudes arranged in gorgeous seraglios, harems and cool-tiled palace interiors was the flow of thrilling stories coming back with French visitors to Egypt during Napoleon’s occupation). The exotic material gave these artists licence to discreetly and lucratively arouse their patrons - elite chaps would gather for private evening viewings of the latest sexy scene from the East.

And what’s remarkable about The Sea Hawk is that we’re now well into the 20th Century and it’s possible for a work of art to so perfectly and uncomfortably restate the orientalism of the 19th. The imagery of the bared shoulders, torn gown and of the knife carried secretly in case of a fate worse than death is carried forward by the filmmaker into the late-colonial period with remarkable fidelity. The Arab characters here are classics of the type - at once lascivious and pious; depraved and up-tight; sinister and richly exciting (and every one of them played by a white actor, natch).

“Farewell, my gallant sea-hawks; may Allah prosper you!”

The final act of the film begins with a kind of diplomatic re-ordering. A formidable British warship, The Silver Heron, patrolling what we assume is the Atlantic coast or the Mediterranean, projecting British power, encounters the Sea Hawk. Realism dictates a quick escape or some kind of deal. The Arab galley would have been sunk in the first broadside. Sir Oliver sees a chance to get his beloved Rosamund home to Cornwall. He leaves his Moorish pals a hero and they salute him, in his robes and his pointy hat, as he’s taken away by the vengeful Brits - to his expected death. The balance of naval sea power is maintained. Everybody knows their place.

And, guess what, on escaping execution - thanks to Rosamund remembering in the nick of time that he has committed no crime (we wonder why she didn’t mention it earlier - I told you she was slightly dim) - Sakr-el-Bahr quickly reverts to cosy Cornish Protestantism, drops the robes and the prayers and is reintegrated to the life of an English noble. The final scene, which is sweetly funny - like the final scene of so many action movies since - sees Sir Oliver re-united with his love, his pipe and his baronial home. A small child completes the picture.

I watched the film on YouTube - the print is good and there’s a bearable Casio organ soundtrack. I’m pretty sure the version that’s on Amazon Prime is the same. This DVD looks a bit dodgy.

Edward Said is our authority on orientalism in art, of course.

I want to acknowledge Wallace Beery as Captain Jasper Leigh. An exceptionally good-value comic pirate sidekick who survives the whole switchback story and winds up retainer to Sir Oliver and Lady Rosamund.

Don’t mix this Sea Hawk up with the Errol Flynn one from 1940.

(sorry, I completely failed to keep it short).

Here's a list of all the top-grossing films since 1913 and here's my Letterboxd list.

And here’s another top-grossing list.