GROSS DISTRACTION - Hollywood Babylon

Crime, sex, addiction, murder and suicide - Kenneth Anger's bible of the dark and perverse in the golden age of the movies.

What came first, the movies or the decadence and excess?

So, in this project, we’re now well into the 1920s. Cinema is a mature form. Cinema is also, of course, the least mature form there's ever been. It's art but it's also sex and crime and addiction and untimely death. We now know that Hollywood in the 1920s was the absolute apex of American transgression (there's a film about it). I won't try to put forward an explanation here. I've read many and they're all pretty thin. There's nothing intrinsically naughty or fallible about the movies or movie people. Nothing in the Californian water.

We can probably agree that it's got something to do with the collision of money, ambition and desperation that often accompanies a gold rush. The fact that the movies essentially carried over the economics and the culture and the relaxed morality of Broadway and the circus and the burlesque must be a factor.

There's no complete explanation. How come, for instance, the equally consequential revolution in business and technology centred a few hundred miles north in what we now know as Silicon Valley seems to have produced nothing more transgressive than a wide range of healthful smoothies and several important new meditation techniques? And no, epic financial fraud and weird libertarian cults do not count.

Hollywood's deep well of wickedness and vanity was essentially a secret until the mid-sixties. It's not that anyone thought Tinseltown was some kind of church picnic or even as respectable as the other branches of show business. Audiences were soaking up stories of desperate, unrequited love, divorce and tragic loss in Photoplay and Movie Weekly and in the trashier sections of their daily newspapers, but the truth was hardly present. Wrong-doing was laundered until it resembled ordinary naughtiness, so as to preserve the fragile box-office value of the stars involved. The darker stories had always circulated too - occasionally surfacing in courtrooms and in autobiographies written in old age - but the iron grip of the studios' publicity departments and the malign control exercised by the moguls over cities and police departments and legislators kept the lid on the darkness for decades.

And the conspiracy of silence was real. No journalist at a respected outlet would go near the stories of drug use, sexual licence, rape and abuse, cruelty and corruption that insiders were aware of, for fear of permanent exile or, worse, losing access to the after-party. Even the famous gossip columnists of the era were essentially authorised chroniclers.

Hollywood Babylon

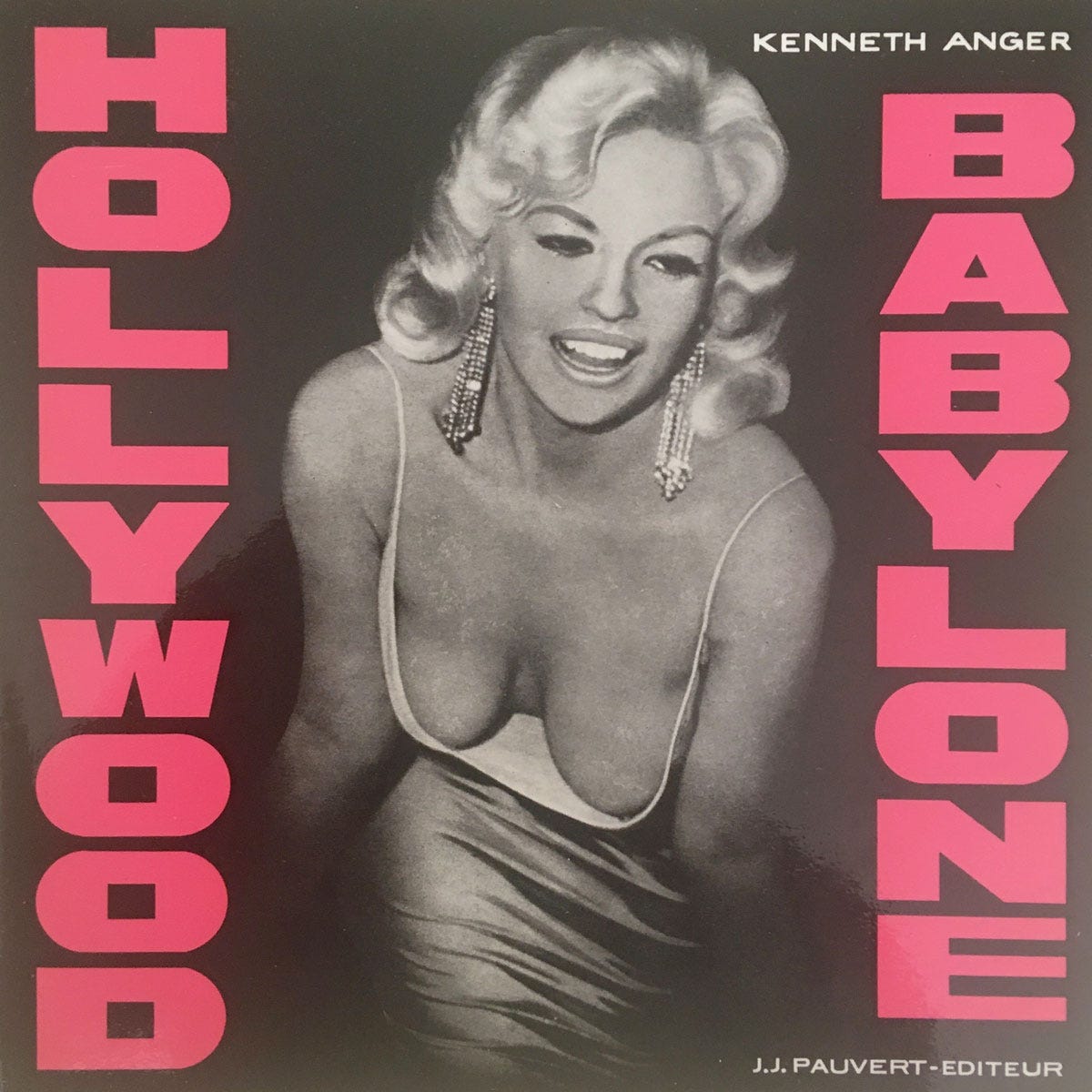

So it took the passage of several decades and the fearless, peerless prurience of a genuine film outsider to bring these stories to light. Kenneth Anger, avant-garde filmmaker, occultist and queer icon, was the man for the job. He wrote a book called Hollywood Babylon. Looking back, it makes perfect sense. Anger was by definition beyond the reach of the studios and the PR machines. He was so far outside the mainstream he was essentially untouchable. We might call him uncancellable. And Anger circumvented the problem of how to get such a book printed by taking it straight to the house of a man known for publishing the unpublishable - Jean-Jacques Pauvert in Paris - the man who brought you the Marquis de Sade and Story of O. Pauvert published various editions of Hollywood Babylone, starting in 1959 (an early French edition will cost you a few quid).

The book’s 1965 American debut, as a ‘brown-wrapper’ edition sold alongside the dirty books, was a disaster - the US edition was banned ten days after publication and was unavailable in its home market for another ten years, when it was published in Rolling Stone Magazine’s imprint - it was by then a hip, transgressive classic (some of the more speculative and/or actionable stories were gone) and began to acquire an audience. I remember the book was a fixture in the small selection of books thought to be a bit edgy - alongside the ‘poetry’ of Jim Morrison and the SCUM Manifesto - that most record shops used to keep at the back when I began frequenting such places.

Anger’s book is not a conventional history. He’s not troubled by the niceties of citation or by silly fact-checking. It's a stream of pithy assertions, usually attributed to sources that can't possibly be checked (because they're dead) or to profoundly disreputable publications, lovers, drivers, hat-check girls, various has-beens with an axe to grind and untrustworthy hangers-on. It's written in the snappy, pulp style of a tabloid:

Professional do-gooders would brand Hollywood a New Babylon whose evil influence rivaled the legendary depravity of the old; banner headlines and holier-than-thou editorials would equate Sex, Dope and Movie Stars. Yet while the country's organized cranks screamed for blood and boycott, the public, unfazed, flocked to the movies in ever-increasing multitudes.

Respectable film people were scornful. The reviews were awful: “…here is a book without one single redeeming merit. It panders to the absolutely lowest element of the reader.” - New York Times, 31 August 1975.

It opens, though, with what I consider to be the best short essay about the origins of the dream factory, its explosive rate of innovation and its tendency to create and then destroy the stars it depended on that I’ve ever read - worth haunting the charity shops for this bit alone.

When word reached [the filmmakers] that nickelodeon crowds all over the country seemed to be flocking to see favorite movie performers known only as "Little Mary," "The Biograph Boy" or "The Vitagraph Girl," the disdained actors, until then thought of as little more than hired help, suddenly acquired ticket-selling importance. The already-famous faces took on names and rapidly-rising salaries: the Star System - a decidedly mixed blessing - was born. For better or for worse, Hollywood would henceforth have to contend with that fatal chimera - the STAR. Overnight the obscure and somewhat disreputable movie performers found themselves propelled to adulation, fame and fortune. They were the new royalty, the Golden People. Some managed to cope and took it in their stride; some did not.

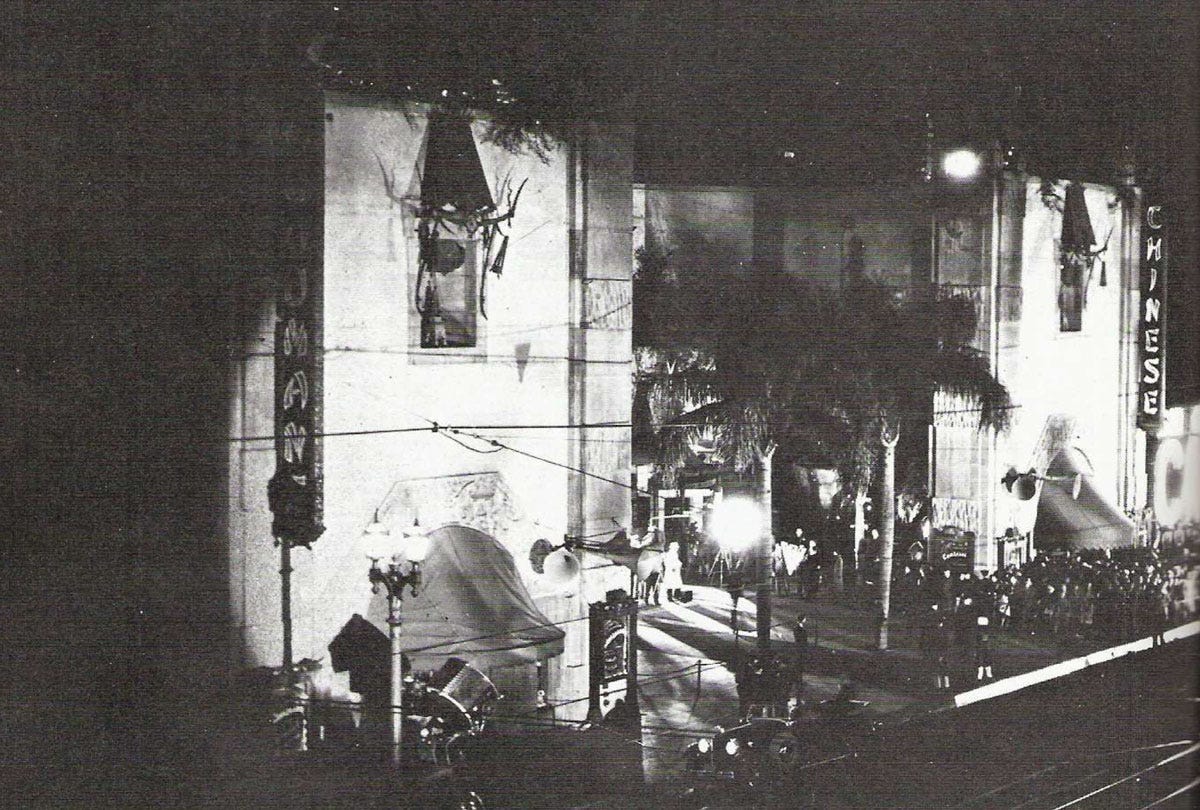

Filmmaker and (rather more careful) historian of the same period Kevin Brownlow - not unused to controversy himself - said he asked Anger what research method he used and was told "mental telepathy, mostly." Hollywood Babylon is illustrated unevenly but with absolute authenticity, using often jaw-dropping, presumably out-of-copyright photographs, private snapshots and publicity stills that are grainy and poorly-composed but always compelling.

It's an unconventional and iconoclastic history of the golden age and its thesis - that human vanity and corruption are not incidental to the Hollywood project but essential to it, that it wasn't the movies that produced the wickedness but the other way around - is convincing.

In part two of this little aside I'll bring you some excerpts from Hollywood Babylon I and II as they relate to the people discussed in the reviews so far. There might be some D.W. Griffith, some Lillian Gish, some Mary Pickford…

Remarkably, the book is still pretty hard to come by. Both part one and part two - published in 1984 - are out of print. You’ll still find part one in the shops but part two - covering the period from the twenties to the seventies - is more elusive.

Anger's filmmaking has gained in stature and, when he died earlier this year, aged 96, there were obits in all the respectable outlets.

Here's Anger talking to UCLA students about Aleister Crowley. I desperately want one of those 'ANGER' jumpers.

There's not much of Anger’s work on the streaming services but there are some Blu-Rays.