GROSS DISTRACTION - books about films

Writing about the movies - dancing about architecture, right?

Next in the sequence of top-grossing movies is another animation, a scary one that I don’t think I really understand - 1940’s Pinocchio. Meanwhile, here are some books…

Books and films. Books in films. Films in books. I think it’s what you’d call a relationship of analogy. Books are like films, films are like books. They exist at the same time, they compete for space in our heads and in the culture but also one came after the other and owes its shape to the one that came before it. The movies inherited the complexity and creative ambition - but also all the social and ideological baggage - of the literature that preceded it. Now they coexist, uncomfortably.

There’s no cinema that escaped its roots in the novel, the popular magazines, the theatre entertainments, the comicbooks and funnies of the previous century. And now we fill our shelves with books that describe back to us the world the movies built.

So, here are some of the books that I rely on for this stuff.

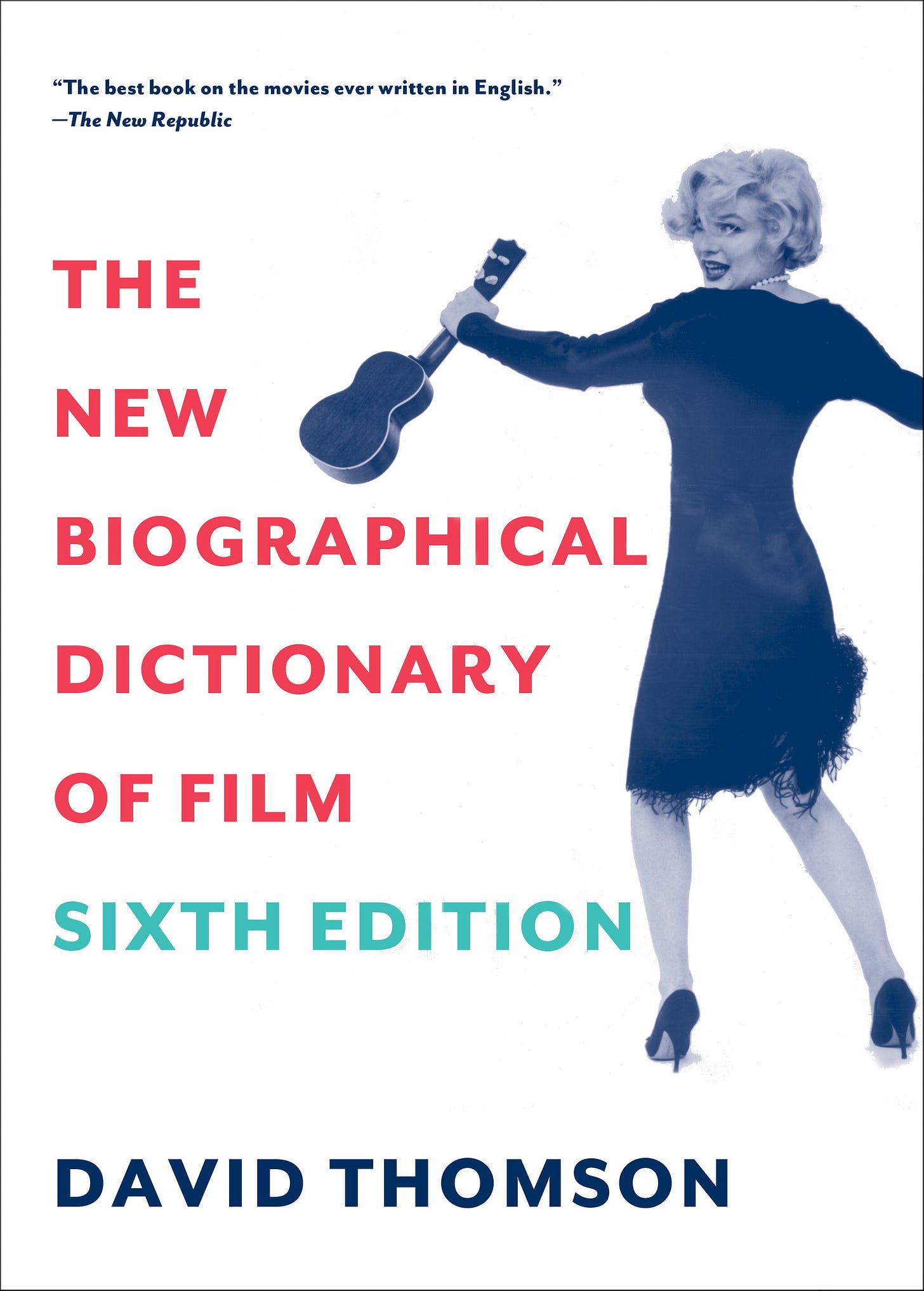

David Thomson

The jewel of the pile. The New Biographical Dictionary of Film. I love David Thomson. If I met him I’d probably swoon or cry or something. He’s a brilliant, literate critic, in the Anglo tradition but conscious of all the others - critical and cinematic - in a way that writers from the English-speaking world are not, usually. Funny, idiosyncratic, always up-to-date. I once went to see Yojimbo at the NFT and was really totally 100% sure that the older man sitting next to me, making notes, was Thomson. I said nothing. What an idiot. I’ve bought everything he’s written, including every edition of this book (the catalogue suggests there will be a seventh, but not until 2027). His book about Psycho is essential. Suspects is a clever, fictional extension of the dictionary. Have you Seen? is capsule reviews of a thousand films. His book about war movies is waiting by my bed now.

Pauline Kael

I think of Thomson as my generation’s Pauline Kael. She was born 22 years before him (in 1919, at the beginning of the explosion of money and creativity that I’ve been documenting here). She grew up at the movies and led a cinematic life, like a Woody Allen character. She managed a cinema in Berkeley, read her arch, highly-subjective reviews on public radio, lived the precarious life of a single mother to a sick child and, eventually, settled at the New Yorker, where she was chief film reviewer for decades. Many subscribers only bought the paper for her reviews. She must have written ten thousand of them, collected every few years in many big books. I’ve got a few of these but if I bought them all I’d need a bigger bookcase. This is a great collection.

Kael really didn’t like Orson Welles much and wrote a long article for the New Yorker in 1971 in which she disputed his authorship of the masterwork Citizen Kane. She documented her theory that the whole thing was really the work of writer Herman Mankiewicz, that Welles was a shallow showman who downplayed his collaborator’s contribution to this work of art. Her theories have been debunked - mainly by Peter Bogdanovich - but the essay is a bracing, common-sense challenge to the whole idea of the auteur. The book version, which is still in print, includes a facsimile of the film’s script and some other essays.

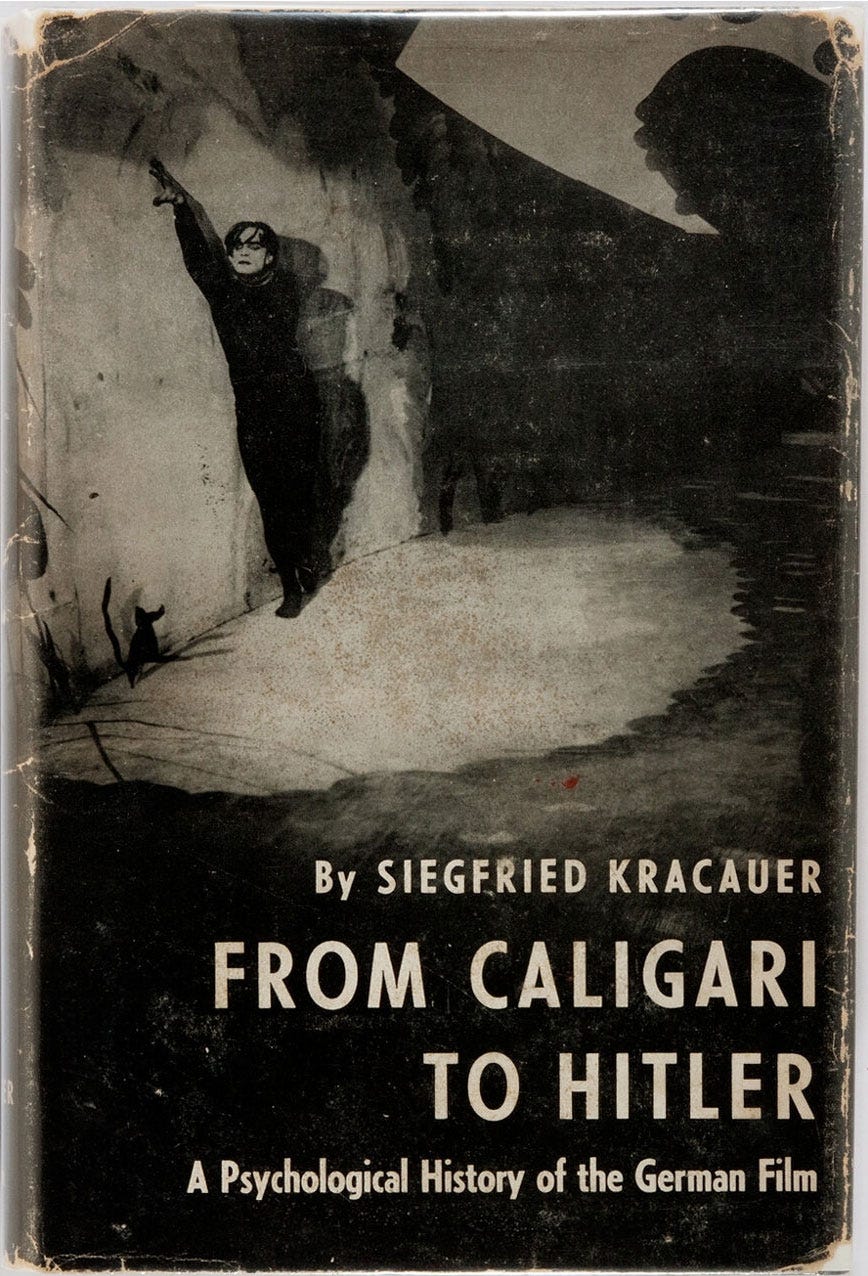

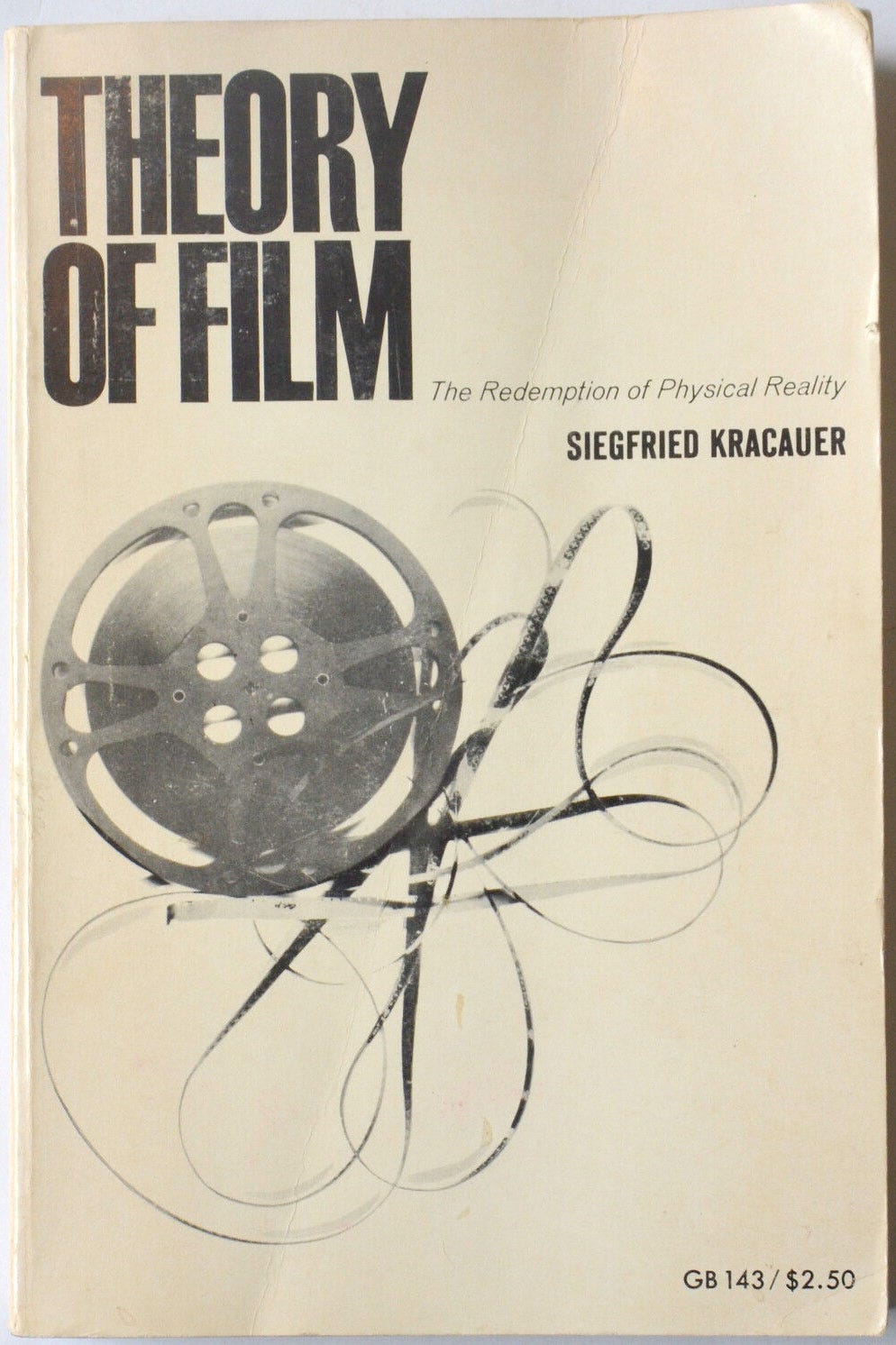

Siegfried Kracauer

Wind back another generation and you get to Siegfried Kracauer, a grand German materialist and a member of the Frankfurt School (gossip: he and Adorno were lovers). His From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film is a mighty text. If you’re going to put the word ‘Hitler’ in the title of your book about the movies (especially one published in 1947) you’d better mean it - and Kracauer profoundly did. In taking the movies seriously as culture and making deep connections between Weimar politics and its cinema he almost in one gesture invented modern film criticism and a whole school of academic film studies.

When I (finally, after three tries) gained entry to the Polytechnic of Central London to study film-but-mainly-photography in the 1980s, I had with me a copy of Kracauer’s film theory book, with its thrilling front-cover image of an unspooled film spool. Within about a fornight it was in a box under the bed. There was really nothing so uncool as a book of Marxist film criticism on a degree course that was all French post-structuralism and radical anti-realism. It’s back on the shelf, of course, now that we’re all happily absorbing the work of opinionated materialists again.

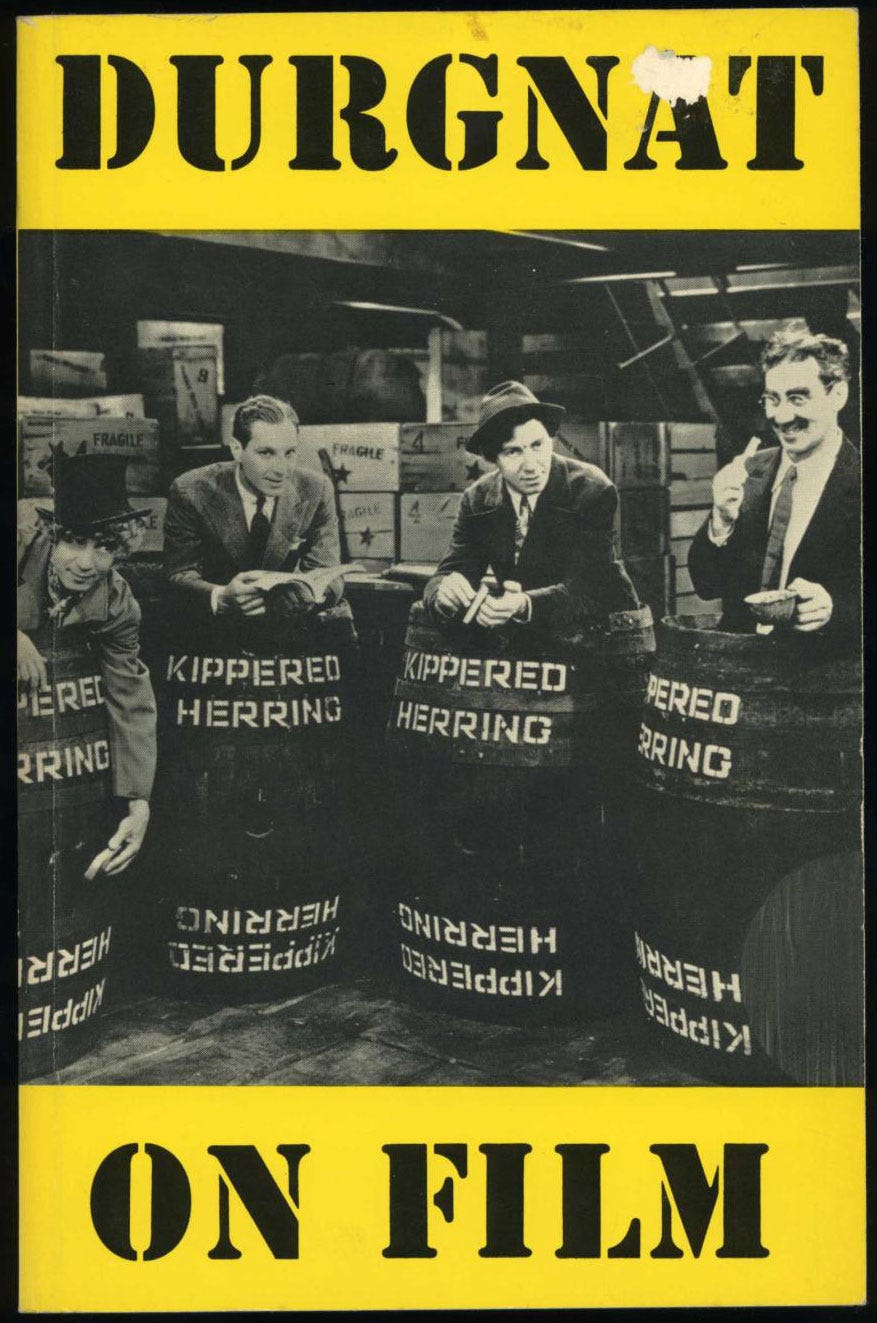

Raymond Durgnat

I knew nothing about Raymond Durgnat until very recently. This may be because I’m incurious or obtuse but also perhaps because he was a kind of pathological outsider who left every club he ever joined and upset everyone while he was there. He was dumped by Sight and Sound after he criticised the magazine’s elitism, dropped out of the Filmmakers Coop because they’d gone a bit structuralist and ultimately left Britain all together to wander the corridors of the American university system (never gaining tenure, of course). Since then I’ve learnt that he’s among the most brilliant stylists in film writing and a provocative critic of ideologies and styles. His critique of Godard (“ocular masturbation”) is brilliant and true, he was a Hitchcock sceptic (he preferred Renoir) when the cult was at its height. His demolition of auteur theory (“a moth-eaten dogma”) is definitive. You won’t find much of his stuff outside the secondhand bookshops these days but you should dig out his book about Hitchcock and the one about post-war British film, both reissued recently. I’d recommend some others but I haven’t been able to find them. He was reconciled with the BFI later in life and they published this excellent collection after his death in 2002.

More reading

I’ve always thought that if she’d lived, American avant-garde archetype Maya Deren would have directed a whole sequence of brilliant screwball comedies for Warner Brothers and then gone on to found a studio and invent a category of blockbuster movies, like Steven Spielberg or someone. But she died at 44. We have the films and Essential Deren, a book of essays •• All those little BFI monographs, written, often idiosyncratically, by all sorts of famous writers and critics, of which there must now be hundreds - covering films from Eraserhead to Do the Right Thing to The Shining •• Peter Bogdanovich’s two brilliant books of interviews, with actors and with directors •• Robert Bresson’s inspiring and infuriating book of aphorisms Notes on the Cinematograph (things like ‘Respect man’s nature without wishing it more palpable than it is’ and ‘A whole made of good images can be detestable’) •• Marilyn Fabe’s Closely Watched Films, which is really an undergraduate textbook - so there’s a chapter about each of the basic film concepts. Very useful •• Andrew Sarris’s big guide to the American cinema between the coming of sound and the New Hollywood, The American Cinema: Directors and Directions 1929-1968 (Sarris brought auteur theory to the USA) •• Lotte Eisner’s deep book about Fritz Lang •• Kurosawa’s beautiful and eccentric Something Like an Autobiography •• Werner Herzog’s profound (and bonkers) book about the making of his profound (and bonkers) film Fitzcarraldo •• Frederic Raphael’s eye-opening account of working with Stanley Kubrick on Eyes Wide Shut •• The Pervert's Guide to Ideology, which is not a book but a film (a sequel, in fact) by Sophie Fiennes, in which Slovenian Lacanian Communist Slavoj Žižek entertainingly finds in the movies the mechanisms whereby our beliefs are reproduced •• And there’s this brilliant book by literary academic Franco Moretti that’s about books and not films but which I found to be a head-spinning account of the origins of the novel - and thus of the movie - in the rise of the bourgeoisie.

David Thomson spoke to NPR about Pauline Kael when she died - “Well, she is the influence, she is the model of modern film writing. I think that really before Kael it was rather a genteel business… often farmed out to people hanging around a newspaper. Kael made it clear that writing about movies had to be passionate, it had to be nearly physical…”

Nine times film critic Raymond Durgnat disagreed with everyone, a BFI listicle.

I also use Wikipedia, to state the obvious. I’ve been giving them a few quid per month for twenty years and I also pay a tiny annual sum for membership of the UK affiliate of the Wikimedia Foundation, which funds and hosts the encyclopaedia, so I can go to meetings and vote on things. Every one of these posts has included multiple Wikipedia links. I consider them to be the backbone of the project - a route to further knowledge. There are all sorts of flaws with the Wikipedia model - it’s the commons of the show-offs and the know-alls - but it’s the best shared learning resource we’ve got. And don’t forget, if you ever see something wrong with a Wikipedia entry or if you spot a gap that ought to be filled, you are encouraged to click the edit button and fix it yourself.

I’ve linked to Bookshop.org (or Amazon) so you can buy these books if you feel like it - although I should say that I think the only really essential one is Thomson’s Biographical Dictionary. No home should be without one. If you do buy one I will make money. Although, to be honest, you’d have to buy a lot of them for this to be meaningful. I mean, feel free. Buy them all. I’ll be very happy.

Various cheeky buggers have uploaded (presumably without anyone’s permission) the short reviews of Pauline Kael, Andrew Sarris and so on to Letterboxd, where you can read them and give them a little heart as if they were by ordinary punters like yourself. My own Letterboxd reviews are here.

Lovely article from Sight & Sound about Raymond Durgnat who was a regular contributor to Films & Filming, a British movie magazine that I have literally just learnt was essentially a kind of gay thirst thing, hiding in plain sight.