GROSS/62 1971 - Diamonds are Forever - “entertainment for men”

Bond is a shabby void (when is MI8 out?).

GROSS is every year’s top-grossing movie, since 1913, reviewed.

DIAMONDS ARE FOREVER, director GUY HAMILTON, cast SEAN CONNERY, JILL ST JOHN, CHARLES GRAY, LANA WOOD; production EON, 1971, 120 MINUTES. Wikipedia, IMDb, Letterboxd.

Listen, I’m not writing another long piece about a Bond movie. So sue me. It’s 1971 and my stupid ‘top-grossing’ rule means I have to write about this dog and not about, er, Get Carter or THX 1138 or Klute or The Panic in Needle Park or Harold and Maude or Dirty Harry or The Last Picture Show or The French Connection or any of the other important films that came out in that year. My Goldfinger alphabet applies pretty well to Diamonds are Forever. Read that. Meanwhile, let’s take a quick look at what’s in James’ wallet.

Friends, the time has come. There are now more than 500 of you and individual emails are regularly read by more than 400 people. So, to keep this project going - and to expland on it - I’m going to introduce a way to pay a little for GROSS. And I’m hoping lots of you will join me and support this gargantuan effort to tell the story of Hollywood through its top-grossing movies. More info soon - Steve

Early in Diamonds are Forever, James Bond is in Amsterdam and the need arises to kill a man and steal his identity. We see Bond’s Playboy Club membership card. Looks authentic, but kind of sad.

It’s en embossed plastic card like most of the ones in your wallet today - an American Express innovation from 1959. Playboy, like Amex, was a self-consciously modern organisation. A cardboard ID would have been out of the question.

The letters ‘UK’ on Bond’s card tell us his home branch is in London, at 45 Park Lane in fact, a building designed by Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius. It is, you’ll admit, at least weakly ironic that Gropius - a fully-fledged member of the Viennese cultural elite who’d been married to Alma Mahler - was a friend and mentor to one Ernő Goldfinger, the Jewish modernist so resented by Bond’s creator Ian Fleming that he named a villain after him (before Gropius departed for the USA he and Goldfinger both had flats at High Point, Lubetkin’s early modernist wonder in Highgate).

The Park Lane branch of the club turned out to be important to the whole Playboy organisation, producing huge profits for two decades as a result of the Macmillan government’s Betting and Gaming Act of 1960 which legalised casinos. Selling cocktails and steaks to sleek international businessmen is a decent business but nothing throws off cash like a casino.

When Playboy came to Britain the company made use of another recent business innovation: direct mail. According to this excellent history of the building in the Architectural Review, “four hundred thousand people, including peers, Senior Service officers, and managing directors, were sent membership packs.” 20,000 took up the initial offer, at eight guineas per year. Bond’s membership number - 40401 - suggests he wasn’t in that first cohort. Loser. Playboy scored valuable free publicity when a former Archbishop of Canterbury wrote an indignent letter to The Times to say he’d received one of these letters.

Direct mail of this kind was another post-war American wonder, with deep connections to the IT revolution and to the new principles of scientific management - and to the fabulous new tabulating computers that were at the same time arriving in businesses all over the developed world. It was invented principally by an affable New York ad-man called Lester Wunderman, who set up shop in the city in the 1950s. He composed elegant and witty direct mail campaigns for coffee companies and for automobile manufacturers. Wunderman’s invention, which was sly and clever and not at all predatory, of course essentially gave birth to the whole targeted advertising nightmare, the dehumanising and coercive ad-tech machine inside which we now live. Thanks, Lester.

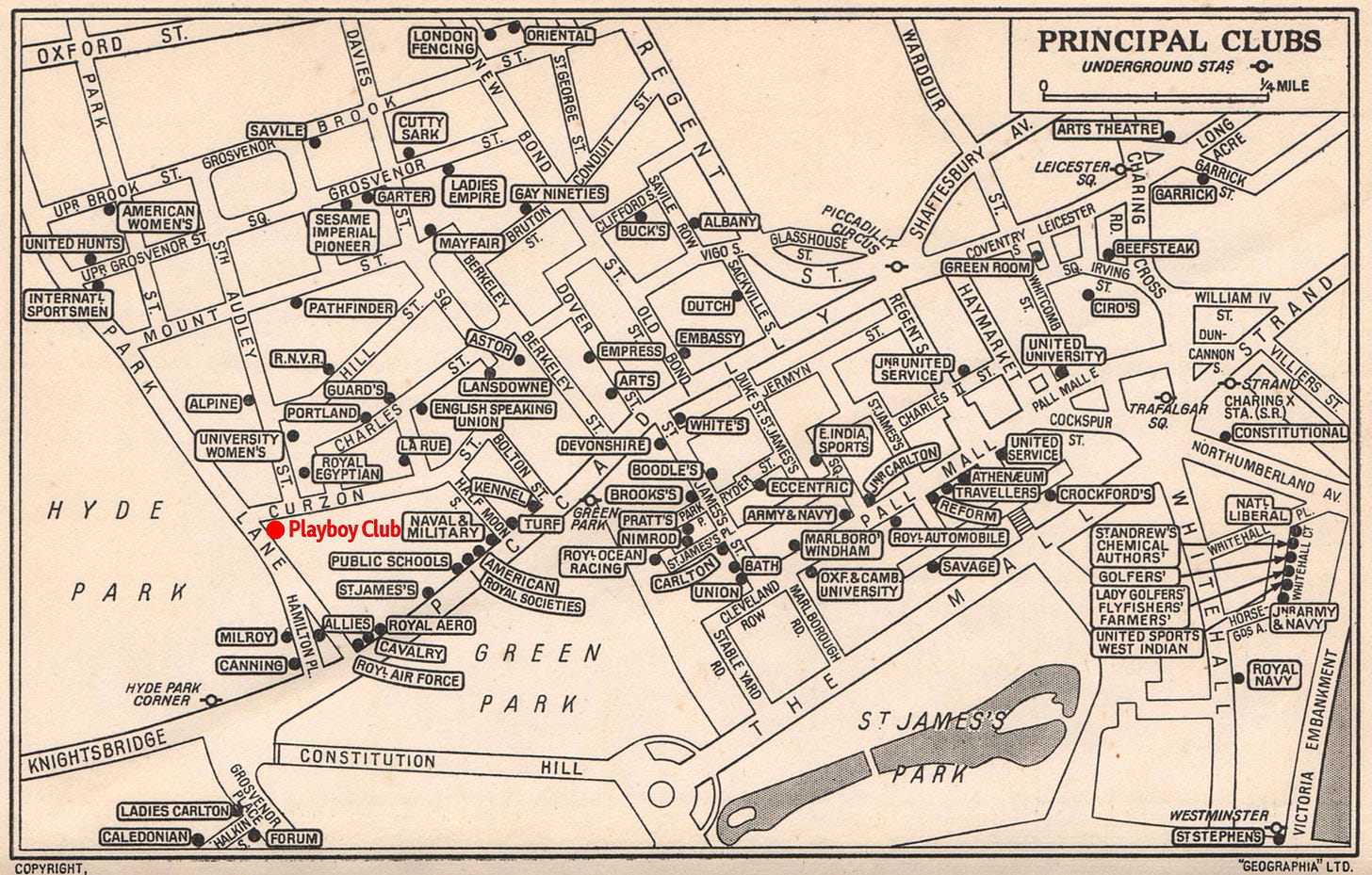

Bond is a British agent from the end of the Imperial era; an aristocratic hard-man from the playing fields of England, but he’s up-to-date. A modernist-Atlanticist decadent. And it’s not just all those gadgets. His plastic Playboy club membership card tells us he’s left behind the dense hierarchy of Edwardian gentlemen’s clubs - dozens of them in the streets to the East of 45 Park Lane, see the map - and adopted the swinging, new American meritocratic form. The Playboy Club will admit anyone who has the membership fee and promises that everything - from the steaks to the cocktails to the manners of the girls at the gaming tables - will be exactly the same in every geographic location (just like McDonalds).

In his clever book about British cinema, Raymond Durgnat writes:

“Bond J. is the last man in of the British Empire Superman’s XI. Holmes, Hannay, Drummond, Conquest, Templar et al have all succumbed to the demon bowlers of the twentieth century, while The Winds of Change make every ball a googlie”

Durgnat was writing in 1970, before this film - the seventh in the sequence - was released, but he’s noted Bond’s sharp divergence from the British upper-class norms of his predecessors, and the radicalism of his accommodation with the new Atlantic elite, with its flat, trans-national culture; its new sources of wealth and prestige, its pragmatic, unanchored, individualist ideology. Bond will conduct himself like an old-fashioned British gentleman-brute but in his wallet there’s a slim plastic card that says he’s a new kind of man all together.

Listen, the next film in the GROSS sequence is 1972’s top-grossing movie The Godfather. I’ll say that again only in all-caps: THE GODFATHER.

“Entertainment for men” was an early slogan of the Playboy organisation.

The Playboy membership card was later upgraded to a heavy metal one.

According to Wikipedia, almost 80% of members of the Playboy Club never actually attended a branch. For these men, membership was presumably purely for prestige or bragging rights or something.

Wunderman’s agency obtained a list of Cadillac owners and wrote to them offering test drives in cheaper but equally fancy Lincolns - unheard-of indelicacy in this period but, it turned out, effective. He wrote about it in his memoir, which is a great read. I met him once - a sweet man and full of stories. I do hope he didn’t go to hell for creating the possibility of TikTok ads.

Diamonds are Forever (along with all the other official Bond movies) is on Amazon Prime, because of that deal. There’s a Blu-Ray.

All these reviews, plus others from outside the sequence, are on Letterboxd.