GROSS/58 1967 - The Graduate - certain natural urges

The first bona fide New Hollywood blockbuster on my list.

GROSS is every year’s top-grossing movie, since 1913, reviewed.

THE GRADUATE, Anne Bancroft, Dustin Hoffman, Katharine Ross; directed by Mike Nichols; 106 minutes; Wikipedia, IMDB, Letterboxd.

It’s 1967 in the United States. The baby-boomers are coming of age. And they hate their parents. Wouldn’t you? They never stop going on about how, when they were your age, they were fighting fascism, from hedge to hedge, across Europe. But now they’ve started another war - not their first - and it’s a complicated, predatory war that self-evidently doesn’t have any of the nobility of that other one. Worse, they’re conscripting you and your peers and shipping them off to East Asia in their tens of thousands. You may already have your papers.

Generations

The boomers thought of their elders in much the way we X-ers (and subsequent generations down to the tragic zoomers) think of ours. We resent them and we’re ready always to assert that not only did they have it better than us but that they have actively interfered in our enjoyment of life - spaffed our inheritance; set the system up to cause us misery, poverty, anxiety.

The Graduate was adopted, by the boomer target audience, as a kind of mascot for the cause. The movie was an enormous hit, running for months with long lines around the block. Something about the naked class war of the thing. About the way the parent-class is set up as antagonist. In this film they’re all rich, but they’re rich in the new American way of leisure and consumerism: barbecues, fancy diving gear, European cars.

Benjamin (Dustin Hoffman) has just graduated from college with distinction. A whole cohort of parents in the fancy Los Angeles neighbourhood he’s returned to - not just his own mum and dad - is recruited to celebrate his achievements and his promise. Parties are thrown; lavish gifts given (and peavishly accepted). Benjamin falls into a loveless affair with one of his parents’ friends, Mrs Robinson. The older people (they’re not old - logically they’re in their forties - Anne Bancroft, playing Mrs Robinson, is 36) are caricatures. They’re archetypes from this new America of neurotic cold-war prosperity.

Prototypes

The thing is, Mike Nichols had tried out most of these characters before - in the improvised sketches he performed with Elaine May, on late night TV and on sell-out tours of theatres.

Nichols and May, both graduates of the influential Second City theatre group in Chicago, invented a whole bestiary of modern Americans and put them in big close-up: petty bureaucrats, emigré doctors, adulterers, psychoanalysts, disc jockeys. Also tortured teenagers like the two in the clip above, negotiating a rite of passage in a way that Nichols would twist and update in The Graduate. For their audience, Nichols and May’s intimate two-ways were about as different from the vaudeville and nightclub comics of their childhood as you could get. Crucially, this is not the spitting, choked-off class anomie of the stage comic, the man in a lounge suit channeling his rage, reflecting the alienation and resignation of his audience.

Nichols and May had been lauded in the late fifties and early sixties for creating a new comic form for this new social context. Theirs is native to TV and the 33-rpm record and the outward-looking confidence of the new generation. It’s self-consciously hip - their first record was an album of comedy improvisations with a jazz accompaniment -and Democrat - they partied with JFK.

The intimacy of this new form meant they had to kick out the third member of their group, not because he wasn’t funny but because for the new media they needed to get up close and form a threesome with a microphone (probably one of the modern electronic ones made by Shure that were transforming the recording industry, making everything sharper and more immediate). For the audience this comedy - which for us is at best charming - was electric, sexually-charged, with a counter-cultural buzz that confirmed their sophistication and their distance from their parents.

Stereotypes

In the movie, Nichols stretches the idea - the uncomfortable, slightly too-big close-up, the harshly-illustrated stereotype, carefully observed. The party scenes, in which Benjamin is surrounded, hemmed-in by boozy grotesques - men and women from a country-club set that he fears he must soon join - are harsh, mediaeval morality tableaux. At one point, Benjamin escapes by running to an upper floor and we feel his elation, rising above this boiling lake of self-satisfied grins.

Nichols can’t muster any sympathy at all for his characters - for any of them - even the leads. So we emerge at the end of The Graduate without having formed a single attachment. The movie inherits the knowing laughter and the smart-arse, off-Broadway cruelty of the comedy act but no warmth, no warmth at all. I want to contrast the centripetal destruction of the relationships in this movie, torn apart by the spinning blades of a consumption-led boom, with the movies that Stanley Cavell calls the ‘comedies of remarriage’ - the 1930s and forties screwballs in which wise-cracking couples split and come back together - It Happened One Night (I love this film. I reviewed it here), The Philadelphia Story, His Girl Friday, The Awful Truth - movies from a period of economic collapse and immiseration and the literal destruction of families and households and communities by poverty. These movies were also, of course, products of the Hays code which literally wouldn’t permit adultery - the conservative rules against which The Graduate and the rest of the New Hollywood defined themselves. But they were also profoundly humane pictures, in which human beings recognise and learn from each other. That does not happen here.

Consumption

To state the obvious, Benjamin’s red convertible has a huge, almost overwhelming symbolic presence here. It’s a vehicle, an emotional weapon, a means of escape but also of quietly desperate return. He’s given this brand new sports car as a graduation gift but in it there’s no joy. We know it’s brand new because this model - the Duetto Spider - has only just been released in the US. The car will become a huge success - and in the 1980s Alfa Romeo will release a tribute edition literally called ‘The Graduate’. At the time of release it costs substantially more than its blue-collar domestic competitor, the Ford Mustang (a car that would acquire its own complicated mythic status in Hollywood) and this is relevant. It’s a chunk of money to spend on your graduating child but it’s wasted on him. Nichols tells us that Benjamin is indifferent. When he drives Mrs. Robinson home - their first encounter - she asks “what kind of car is this?” Ben replies, “I don’t know.” So it becomes another index to his bitterness and confusion - driven into the ground in his bleak pursuit of… what is it he’s pursuing? Not love. He doesn’t care, nobody in this movie cares.

Composition

I should ease off. I mean I do this all the time: I get a theme and then it runs away with me. The cruelty and hermetic individualism of The Graduate gets me down. But I should note Nichols’ celebrated compositional brilliance, his ease with the form. So much is smart and tidy about this movie.

The edit is a craft study. An audio engineer friend told me to listen closely to the way the sound is cut just before the image, introducing a tension. This clip above is from the end of a famous sequence - three or four minutes, without dialogue, cut to Simon and Garfunkel. It’s clever, circular, facile. I’m tempted to shrug.

This movie seems to be loved by everyone of a certain age but ask them why and they won’t know. It’s probably the music, which has replaced the images in many people’s memories of the film, ameliorating its shallowness by substituting melancholy. The soundtrack is a complicated story: there’s specially-composed music by Dave Grusin, and some adapted for the movie by Paul Simon, but Mrs Robinson couldn’t be nominated for an Oscar because it wasn’t strictly an original song. The soundtrack album, consequently, has a lot of music that’s not in the movie.

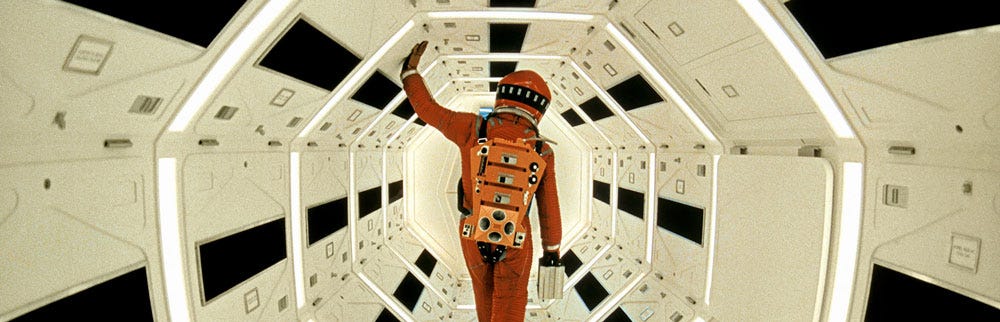

Next up, for GROSS, another movie with famous music - and none of it specially-composed (and some of it used without permission): 1968’s biggest movie, 2001: A Space Odyssey (and a warning: I don’t have a good feeling about this one either. Sorry).

Who is the best human being in The Graduate? I don’t mean the best character - that’s obviously Mrs Robinson. I mean the best person, the most complete, identifiable, moral being. It’s Mr Robinson, played by Murray Hamilton (later the Mayor of Amity Island). Human, forgiving, self-aware, aware of others too. In this movie fully of dead-eyed narcicists he’s a paradox.

Nichols was a reluctant filmmaker (first it was acting and comedy, then theatre directing then, only as third choice, the movies) who would become a very complete filmmaker. Some big twentieth-century touchstones in his credits: Who’s Afraid of Virgina Woolf?, Catch-22, Silkwood, Working Girl…

The Graduate is on Amazon Prime, where I watched it, but also everywhere else. There’s a 50th anniversary Blu-Ray which has a lot of extras. I feel like there ought to be a fancy vinyl edition too but there’s just this ordinary one.

The Graduate is on the front cover of Scenes from a Revolution, Mark Harris’s entertaining book about the 1967 Academy Awards, the moment the New Hollywood became, you know, a thing (another Nigel Smith tip).

Stanley Cavell was a philosopher who concerned himself with popular movies. In the introduction to Pursuits of Happiness: The Hollywood Comedy of Remarriage he recalls the impatience of his academic friends at a seminar when they learnt he wanted to talk about a Capra movie and not “…something cinematically high-minded, something sad and boring, something foreign or foreign-looking, or something silent.”

Thankyou for an insightful and nicely written piece. I was lucky enough to see this on the big screen a few years ago great experience, I was struck at just how lurid and vivid is the colour and lighting. Like a shop window display...

In reviewing this boomer touchstone, I got down Douglas Coupland’s book ‘Generation-X’. I thought he’d have something interesting to say about the baby-boomers. But no, not a thing. The man who literally invented Gen-X (anyone born in the sixties, he says) doesn’t mention the preceding generation, the one we’re all obsessed with, the one that ruined everything. So I’m thinking ‘maybe we’ve got it wrong, maybe it’s our own fault’.