GROSS/48 1957 - The Bridge on the River Kwai - the childish delusion of the omnipotence of thought

Public school fantasies take on brute reality in the jungle.

GROSS is every year’s top-grossing movie, since 1913, reviewed.

THE BRIDGE ON THE RIVER KWAI, director DAVID LEAN, writers CARL FOREMAN, MICHAEL WILSON (book by PIERRE BOULE), cast ALEC GUINNESS, WILLIAM HOLDEN, SESSUE HAYAKAWA, JACK HAWKINS, production HORIZON PICTURES (producer SAM SPIEGEL)/COLUMBIA PICTURES, 1957, 161 MINUTES.

I decided that the previous film in this sequence - DeMille’s tedious, toxic time-waster The Ten Commandments - didn’t merit a big treatment here, so I just whinged about it in one long paragraph. Of course, it really does merit a big treatment. I just didn’t feel like it. I’ve had enough DeMille. Luckily that was the last one. No more DeMille. All done. Several more sodding epics to come, though - Ben Hur, Spartacus and The Bible FFS. Then it’s the new Hollywood and everything gets a bit more godless and sexy.

You know when you spend a bit of time with a film (or a book or whatever) that you’d always held an essentially neutral or even positive position on but, in doing so, you come to hate it with a cool passion, as if it were the most ridiculous and wicked thing ever made? That.

This movie needs the treatment. It’s asking for it. Asking to be re-inserted into history, I mean. David Lean was a brute - he never saw a historic event he wouldn’t de-historicise or strip of its material context for the lols. In The Bridge on the River Kwai he lifted a huge story - a story on a global scale - geopolitical forces, collective action, terrible suffering - up out its historic context and gave it to an individual (two of them, really).

The Kwai is a real river. During WW2, the Japanese occupying forces really did push a railway through the dense Burmese jungle and across that river and they really did force thousands of prisoners of war - and tens of thousands of other captives - to build it. The human cost was vast.

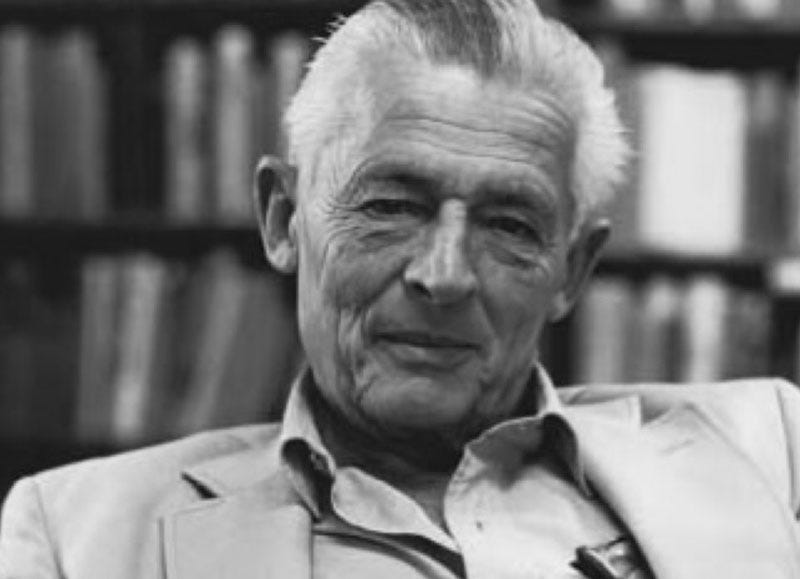

Ian Watt was there. He was a British infantry officer, captured with the whole Singapore garrison in 1942 and forced, along with his men, to work on the Burma railway. It was a singularly grim experience. He watched hundreds die from mistreatment and sickness and men beaten to death for trivial acts of insubordination. He saw the hideous ill-treatment of the Asian prisoners enslaved alongside the soldiers and he almost died from malnutrition.

Survivors of the Burma railway were vocal about their objections to the movie. Writer Carl Foreman reacted furiously, though, threatening to send a six-page telegram to the BBC after he saw a documentary in which Watt outlined the egregious inaccuracies of Kwai.

Watt, unlike many of the prisoners who made it home, wasn’t rendered mute by the experience. He wrote about it and said that what he learnt about the exigencies of survival contributed to his worldview as a literary academic - to a kind of tough-minded materialism, impatient with fantasy and with the indulgence of fantasy.

As a British academic, of course, he was obliged to maintain a certain empirical rectitude, an ironic distance from all the continental abstraction and from the florid disciplines of ‘theory’ that were emerging as he began his academic journey.

Watt became a kind of bridge in his own right - sympathetically linking the straight-backed Leavisites with the structuralists and with the Frankfurt school. He knew and liked Theodor Adorno, cited Lukács, Durkheim and Weber, quoted Barthes and worked in an American university system shaped by the European thinking. He taught the novel at Stanford, in a department that was developing a radical new analysis of the form, but retained his officer-class reticence and refusal of abstraction throughout.

Filmmakers often take inconceivably vast events like the war in the Far East - the sweep of history - and make of them individualist adventures, romps, tales of heroism and resourcefulness (see practically every Hollywood war movie). And we don’t usually object. We allow that an artist can give us the mass via the individual. The historic via the day-to-day. And we’re not sceptical about this. We somehow buy the idea that a single performer (RADA/Strasberg-educated, natch) can somehow plausibly condense the experience of dozens or thousands or millions.

But it’s hard. Collective experiences and long-duration events are discontinuous, unboundaried, often not recognised as single, describable entities at all. The thirty-years war, industrialisation, the 1832 Paris rebellion, the Blitz, the shallowness of the nineteen-nineties, coming-of-age, the miners’ strike… Things that might not even have Wikipedia entries. Tricky things to collapse into a 90-minute narrative.

Never historicise

And there’s a counter-tendency that strips the history out of the story, removes the story from history. There are too many examples to list. American cinema does almost nothing else (scroll back through the GROSS archive, you’ll see what I mean). This is the main thing I’ve learnt from ploughing through Hollywood’s history in the way I’ve been doing here, if I’m honest. Hollywood systematically de-historcises, individualises as if its life depended on it, as if this were its primary function (which might actually be true).

Even the greatest Hollywood characters - the most influential on their surroundings, on the lives of others - are ripped from the various continuities they depend on and that they produce - from history and society - as if they could stand outside them, like marble statues put up just outside the city. Michael Corleone, Margaret Thatcher, Sergeant York, Cleopatra, Charles Foster Kane - mysteriously disconnected from the processes that produced them.

David Lean is one of the most brilliant practitioners of this de-historicising art. He perfected it in his later epics. These movies are the most perfectly unanchored ‘historic’ texts in the canon. In Lawrence of Arabia, when Omar Sharif emerges from the haze on his camel, alone against the vastness of the desert, he’s also alone against the vastness of history. He gets down from his camel and confronts O’Toole’s Lawrence with no greater connection to the material circumstances than Obi Wan had when he took on Darth Vader.

Ian Watt’s objection to Kwai was deeply-felt. Really a cold fury. Lean hadn’t just got the story wrong - simplified or overstated it in the ordinary manner - he’d changed its terms completely. Specifically, he’d taken the central British character - General Nicholson, played by Alec Guinness - and turned him from a practical leader and a humane problem-solver into a mercurial eccentric and a traitor.

This crime against truth was a joint enterprise. The book on which the film is based - by Pierre Boulle - had already simplified and minimised Toosey’s humanity and Lean’s producer, Sam Spiegel, essentially the archetype for the philistine Hollywood producer, went further, gleefully reversing its message.

Nicholson’s model in the real world, Colonel Philip Toosey, was a remarkable man. In the camps on the Kwai he saved countless lives and made life easier for prisoners along the whole length of the railway by stepping in to organise the operation. He arrived at an agreement with his camp commandant (and later with others) and under his practical regime deaths in the workforce fell to almost none, the routine was less brutal, food and accommodation improved. Toosey’s intervention was essentially to substitute something resembling 20th Century managerialism for the older, cruder military logic of the Japanese Imperial forces. This British colonel was a modernist, a Fordist even. The result of this greater efficiency: fewer deaths and less misery.

Lean’s colonel does a much simpler thing: he swaggers around the camp like an Ealing Comedy dame and collaborates with the enemy. We are ultimately disgusted with this pig-headed bureaucrat’s dim-witted failure to understand his situation. And in the movie he only acknowledges his error in the last seconds of his life - saying “what have I done?” as he realises what is about to happen to his beautiful bridge.

Officer class delusions

We’re conscious, throughout the movie, of hierarchy. But it’s taken for granted. It’s the absolutely hard-wired hierarchy of the war film. The audience understands that military hierarchy is different from the other forms we live with. Workplace hierarchies are an entirely modern, post-industrial invention but this workplace (the railway) is governed by an older hierarchy: the British and Japanese military systems - both essentially pre-modern in nature, determined by the unquestioned logic of rank, discipline and belligerence.

Military hierarchy is resistant to modernisation. In the Soviet Union the soldier committees lasted a few years but were pretty soon replaced with something that looked a lot like the rigid structure that came before. Zhukov pushed back the vast, sophisticated German army using essentially the Czarist military model. All the armies of the second world war complied with this norm. No army since then has varied it much. There’s no DEI in a foxhole.

In Kwai the ordinary ranks are barely present. We hear them yelling and cheering (and whistling obvs) - and we see them working but Lean finds them uninteresting. They’re secondary to the story, essentially a chorus. The working class soldiers provide a kind of shifting khaki backdrop, a rhythmic, marching counterpoint to the more cerebral officer discourse - left-right left-right left-right… Attention!

“…it’s the schoolboy’s perennial dream of defying the adult world. Young Nicholson cheeks the mean, old headmaster - the Japanese camp commander called Saito - and of course he gets a terrible beating but then the other students kick up such a ruccus that the headmaster just has to give in, Nicholson is carried back in triumph acorss the playground and in the end becomes the best student body president Kwai High ever had.” - Ian P. Watt

This is an officer-class story. Early in the film a copy of the Geneva Convention is produced and our Japanese camp commandant throws it disdainfully in the dust. It’s the third convention, agreed in 1929, with clauses about the treatment of prisoners of war. Nicholson reminds the commandant that, under its terms, officers may not be forced to work. There’s a disagreement and Nicholson is punished. Meanwhile, the enlisted men carry on working.

And into this top-heavy story Lean inserts a fabulously preposterous individualist hero - a war movie staple - considered by Watt and other veterans to be the final insult: a sexy American with blue eyes, washboard tummy and an attitude. William Holden plays fake Commander Shears, basically a character from Catch-22 (he even has a plan to achieve a medical discharge on grounds of insanity). He intrudes on this stiff-upper-lip-fest, bringing American insouciance to the party. His contribution cuts across the hierarchy. We enjoy his cool disdain for the British way and he makes a kind of dialectical pair with Guinness, as they converge for the movie’s climax in the jungle.

Logic in adversity

Ian Watt’s ultimate objection to Kwai is that of a materialist. His admiration for Colonel Toosey, the man on whom the movie’s hero is based, is too. The colonel saw the material circumstances of the camps and the railway - the harshest possible context, the cruelest and most coercive situation a human being could face, and he responded without illusion. Watt says:

He observed all the circumstances of the life around him and then used his imagination to see how the experience of the past, in history, might help the present and prepare for a better future. He knew that the world would not do his bidding. He knew that he could not beat the Japanese. He knew that on the Kwai, even more obviously than elsewhere, we were, for the most part, helpless prisoners of coercive circumstance.

For Watt, Toosey was a model for the cool-headed overcoming of adversity - the rational analysis of a situation - and Nicholson, the movie version, was a hysterical parody of the real Colonel - a swaggering fantasist wedded to rules, out-dated principles and ridiculous, counter-productive fantasy. On the Kwai:

…all our circumstances were deeply hostile to individual fantasy. Surviving meant accepting the intractable realities that surrounded us and meant making sure that our fellow prisoners accepted them too.

Watt here, writing over forty years ago, anticipates a very contemporary situation. The situation in which we find ourselves, in fact. Where radicals and progressives swagger and fantasise - inventing and enforcing new rules, making pointless gestures - with no apparent ability to analyse rationally or act logically - and the only practical people on the scene are the reactionaries and the parasites.

Watt wrote about the movie very soon after its release, marshalling the objections of his fellow survivors but also his unique literary-historical take. His intervention infuriated the filmmakers. In this fascinating 1979 lecture he gave about the Kwai he says that screenwriter Carl Foreman demanded a retraction but didn’t get it (a lot of the material in this essay comes from Watt’s lecture).

Watt respected one aspect of Kwai - “…on March 12th 1957, a beautiful bridge, that was then the largest structure in Ceylon, that had cost a quarter of a million dollars to build, was blown up, with a real train crossing it. Building a bridge just to blow it up again so that the movie public won’t feel frustrated seems an unbelievably apt illustration of Boule’s main point about how our society employs its awesome technological means in pursuit of derisory and destructive ends.”

This review of a recent biography of Ian Watt in the LRB convinces me I ought to learn a bit more about the man’s work.

Watt and Lean were obviously very different men. One a soldier and an academic; one a Quaker and an artist. But from their photos above tell me it’s not obvious that they have the same origin - in the British upper class.

Kwai is a perennial hit. When the movie was finally shown on TV it broke records. 72M people watched it on CBS in the USA in 1966. The whole thing, with ads inserted, ran to over three hours. The BBC paid a vast, record-breaking £125,000 to show the movie on Christmas Day 1974 (the following day the BBC broadcast a documentary made by survivors of the death railway).

Watt’s The Rise of the Novel is still in print and still taught, but widely considered uncool because it comes from the period immediately before theory problematised everything.

Watt quotes Roland Barthes saying “A myth is a story which has been elected by history.” He’s paraphrasing “myth is a type of speech chosen by history” or “le mythe est une parole choisie par l'histoire,” from the essay about The Family of Man in Mythologies.

Watt also makes use of psychoanalysis in his criticism of Kwai - further evidence of his connections with post-war lit theory - and is referencing Freud when he talks about “the childish delusion of the omnipotence of thought.”

You’ll want this t-shirt, with Fredric Jameson’s phrase ‘always historicize’ in the Google font (and with the American spelling obvs). It comes in all possible sizes and styles (and there’s 20% off with code BLKFRIDEAL01 if you order sharpish).

Kwai is on Amazon Prime (in a 4K restoration) and there are various good Blu-Rays.