GROSS/20 1931 - Frankenstein, apotheosis of camp

James Whale, a grand figure, an outsider, a visionary and a cheeky bastard - invented a genre… and then another one…

Gross is every year’s top-grossing movie, since 1913, reviewed.

FRANKENSTEIN, JAMES WHALE, UNIVERSAL PICTURES, 1931, 70 MINUTES.

It’s hard to write anything coherent about 1931’s top-grossing movie. Even once you’ve added the sequel, Bride of Frankenstein, to the mix and made a glorious pair it doesn’t get much easier. These movies have been so mythologised it’s hard to provide anything better than cliché.

When we discuss a film - a phenomenon - like Frankenstein, we’re rendered uncritical, predictable, boring. It’s been absorbed into the culture, obscured by its notoriety. It’s almost impossible to offer an opinion.

Genre number one. Literally the first gothic horror movie

But Frankenstein is a great movie - a tightly-organised 70-minute thriller in a completely new genre, with a superb, repertory-company cast (Whale’s friends, his loyal crew) and expressionist art direction that’s so sharp it makes you giggle with pleasure. The opening scene somehow collapses together a century of gothic graveyard imagery to create a montage Poe couldn’t improve upon.

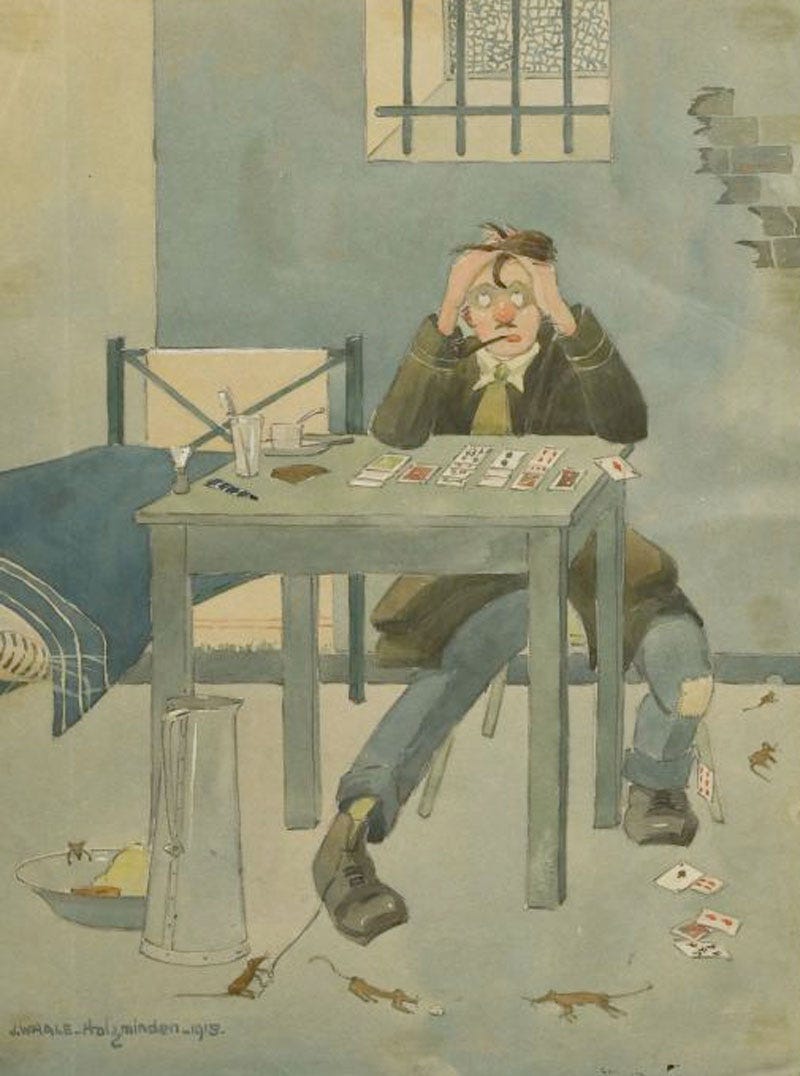

Let’s go back and get the West Midlands bit out of the way. James Whale was a working class kid - a grafter, half-educated like most poor kids of this era, ambitious, creative - born in Dudley, the Capital of the Black Country in the 53rd year of Queen Victoria’s reign. There are brass plaques and memorials all over town. Like so many of these early cinema geniuses, there’s a gutsy storyline about adversity overcome. Serving in Flanders in 1917 he was taken prisoner. In the camp he became a poker wizard and, it’s claimed, later cashed in all the IOUs from his fellow Prisoners of War to fund his re-entry to civilian life.

His drawings from that period are beautiful and sad. He’s observing his fellow soldiers and the officer-class with amusement and affection. It’s dry and unimpressed. And we find this in his later work. Even at his silliest there is irony. Even at his most serious some broad, self-undermining humour. Whale’s whole oeuvre is self-aware, secular, modernist art.

James Whale directed a dozen other (mostly) subtle and charming films. He became a cause célèbre because everyone knew he was gay and because of his unashamed, happy concupiscence; also because he died in the approved Hollywood manner - in his own swimming pool - and the suicide note wasn’t made public for decades so there was speculation.

Somewhere in Europe

Because I’m a dweeb, I always find myself returning to the class composition and the political economy and the history in these old movies - who are these people? Where are they? What’s the constitutional and democratic set-up here? Shelley sets her novel in the 18th Century, in a fairly specific early-modern Switzerland/Germany. Whale’s film is less precise. We’re somewhere vaguely in Europe and, of course, it’s Hollywood’s Europe - an undifferentiated pre-Westphalian locale (it could be Freedonia).

Non-speaking roles wear identifiably peasant apparel - and dance holding hands in the town square - while the gentry, up in the castle and in the Baron’s stately home, wear modern clothing - lounge suits, gorgeous eveningwear and tweed.

This noticably awkward, sci-fi relationship to time is not a deliberate time-slip device. It’s classic Hollywood narrative sloppiness; style over substance. It’s the sloppiness of pop literature too, of course, it’s not unique to the movies. Whale wasn’t looking for consistency here - “I need an approximately Mediaeval village, something Tyrolean. Is there one on the lot?”

And the elite men and women, in the fashions of 1930s America, lord it over the apparently pre-modern peasantry in a town with no motor vehicles, no telephones and no electric light (plenty of electricity up in Victor Frankenstein’s lab, of course). My head is spinning.

We’re adrift in time but the state is present in an ancient form - that of the Burgomaster - the town’s Mayor. Like all movie Mayors he’s pompous, ineffective, yelling from a balcony in the town square - basically Quimby. Mayors are intermediate figures - politicians but also managers, members of the elite but also bureaucrats. The role precedes capitalism. They were reeves, bailiffs, administrators of land and property for a thousand years, but crucially they were always in service of the feudal lord.

This is carried forward to the present day. Mayors, sometimes elected, very often appointed, always represent capital and will always choose profit over wellbeing. In Frankenstein the Mayor, played by Lionel Belmore (another Brit, from Wimbledon) serves as a lieutenant to the Baron, communicating his instructions, leading the mob on his behalf. His hat gives away his status - he’s wearing a modern fedora, like the aristocrats, and not the kind of Tyrolean feathered cap the peasant men have. He’s a cut above, a petit-bourgeois.

The Frankensteins are uncomplicatedly aristocratic. The Baron (our hero’s father) orders the peasants around like serfs. Servants and townspeople line up for his patronage. Around the house he wears a soft smoking cap with a tassle - the decadent, chilled-out Ottoman look was an aristocratic trend in the Victorian era and the early 20th Century.

There’s no evidence of religion in the town or the big house but back at the beginning of the film, in the graveyard, we saw some burial rituals that definitely looked a bit Catholic - there was some latin and a swinging bell. Aristocrats with these decadent habits couldn’t possibly be protestants. Luther has evidently had no impact here, despite our location, so close to the seat of the reformation.

The well-regulated militia

The police action against the monster is undertaken exclusively by the townspeople, of course, rallied in a standard-issue monster-movie rabble. Torches, pitch-forks, hunting rifles. If the town has a police force they’re cowering in their barracks or on an away-day. Is this a militia? An armed group defending its own interests? Or a pressed force fighting for the people in the big house?

The monster is a worker, made in a laboratory by an entrepreneur, but a worker nonetheless. He’s a unit of labour made by what for capitalism would seem to be the ideal method - by recycling expired units of labour, workers that are beyond use and have, in fact, been buried in the ground by other workers. If all workers could be recycled in this way and returned to the labour pool after their death then that would represent at least a doubling of capacity (more if it’s possible to repeat the process, of course, or if a single corpse can be used to make more than one new worker).

This is the ultimate, concealed content of the story. Shelley’s final departure from Romanticism is here, in this mechanisation of the reproduction of labour. Welcome to the machine age. When the Baron and Mayor send their mob to destroy the monster they’re despatching feudalism against the future, the ancien régime against capital. It’s the final conflict of the old world and the new.

Here comes the bride

Bride of Frankenstein, the sequel to Frankenstein, released in 1935, is sillier, even more knowing. A director of Whale’s wit couldn’t have done otherwise.

There was no way he could follow Frankenstein without dialing-up the camp, the slapstick, the screaming and thunderclaps, the gurning and twitching, the truly spectacular hairdo. It’s not a masterpiece but it’s a worthy, comic coda to one.

At the beginning of the film, by way of an epigram, we meet Frankenstein’s author Mary Shelley herself, but also Percy Bysshe Shelley and Lord Byron. Whale could have left this bit out and got straight into the action but it sets the ironic, self-examining tone. Mary is played by Elsa Lanchester who also plays the bride herself (neither is a huge role and, of course, they never meet so this is very practical casting). In this scene, Lanchester embroiders but she’s anything but serene. She seems nervous, demented in fact - it’s as if she’s trying hard to suppress the squeaks and robotic ticks of the monster she’ll portray later.

The scene cleverly sets up the sequel: Whale is saying something like “you enjoyed my first go at Frankenstein, here’s another one - but we’ll need some explanatory front-matter otherwise you’ll think I’m just a hack.” The three poets add nothing, except the Hollywood awkwardness of having to introduce themselves to audiences unfamiliar with 19th Century Romantic verse, in a high-ceilinged drawing room, in a thunder storm. “I like to think that an irate Jehovah was pointing those arrows [the lightning] at my head, the unbowed head of George Gordon, Lord Byron, England’s greatest sinner” and so on.

No God

The script asks Mary to provide the standard apologia for her great novel - the one that became orthodoxy and that you still hear today: “…my purpose was to write a moral lesson: the punishment that befell a mortal man who dared to emulate God” but we know there’s no God here or that He is only nominally here - as a placeholder for the status quo. There’s a neat ‘previously…’ montage but we’re all just waiting for the story to get started. Which it does, right away. Dramatic transition… Boom.

The film’s been described as a ‘gay classic’ but this is a mis-reading. It’s not gay but it is hyper-aesthetic, a stylised cathedral to artifice. It’s exactly what Susan Sontag had in mind when she wrote: “Camp is a certain mode of aestheticism. It is one way of seeing the world as an aesthetic phenomenon. That way, the way of Camp, is not in terms of beauty, but in terms of the degree of artifice, of stylization.”

Elsa Lanchester’s bride is profoundly and effortlessly camp. She may be the most camp character in the early cinema. We cannot take her seriously, she cannot scare us, she cannot do more than delight us.

We should probably be grateful that Whale wasn’t asked to make a third Frankenstein. It would have been exponentially more camp and would probably have caused the celluloid to melt or burst into flames in the can. Of course, there was a third film in the sequence but it was made forty years later by Mel Brooks. He found in these movies a sequence of perfect, pastiche-ready tableaux - he really just had to write the gags.

Genre number two. Literally the first scary-house-in-a-storm movie

Between Frankensteins one and two, in 1932, James Whale directed another gothic gem - The Old Dark House - which is a better film than both of them. There’s more genre innovation here too. This is really the first ‘scary house in a storm’ movie. It’s based on a novel by J.B. Priestley (whose name - stunningly - is spelt wrong on a huge card in the opening credits). It’s a splendid, funny, humane film that’s packaged as a horror movie but really isn’t.

This post is already much too long. More about The Old Dark House in a later email. Next week von Sternberg’s Shanghai Express with Marlene Dietrich and Anna May Wong (who starred in Piccadilly, which I wrote about here).

Frankenstein, Bride of Frankenstein and The Old Dark House are all on Amazon Prime.

As you’d expect there are plus-fours, universal indicator of rogueish masculinity, in Frankenstein. I’ve written about plus-fours before.

Worker robots are everywhere - 3.6 Million of them apparently, although none so far are made from recycled workers. Musk is trying to create a bipedal one to freak us out completely, of course.

Terrific long article about the Bride of Frankenstein, on Janne Wass’s sci-fi movie blog.

Elsa Lanchester was liberated by the Bride of Frankenstein. Once she’d accepted that role she was never going to be offered a conventional female lead again. So she took her own path. Here she is talking about husband Charles Laughton.

You can get Sontag’s essay about camp in one of those tiny Penguin editions so it’s only three quid - or 99p for the eBook.

Here's a list of all the top-grossing films since 1913 and here's my Letterboxd list and here’s another top-grossing list.