GROSS/42 1951 Quo Vadis? part one - Il Duce, Il Divo and the Roman Empire

Cinema in Europe after the war was an epic drama

Gross is every year’s top-grossing movie, since 1913, reviewed.

QUO VADIS? Director MERVYN LEROY, cast ROBERT TAYLOR, DEBORAH KERR, LEO GENN, PETER USTINOV. production company MGM, released 1951, 171 MINUTES.

Listen, before I consider this sanctimonious potboiler, you need to understand a few things about the context. Some of this stuff is going to make your head spin.

Il Duce

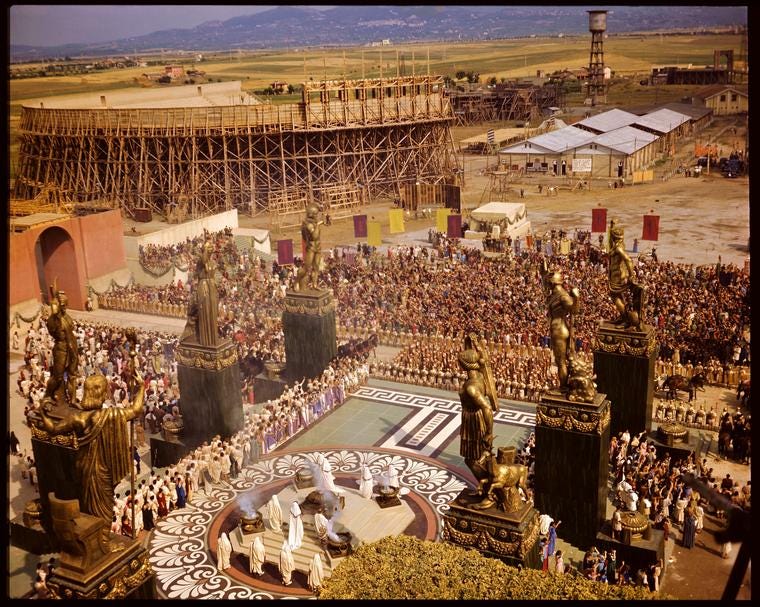

To start with, Quo Vadis was the most expensive production ever at the time of its release - $7M (about $90M in today’s money). On first release the movie made over $21M internationally. A three-times multiple of production and marketing costs is roughly what you want from a big-budget movie so it was considered a hit. In fact Quo Vadis essentially rescued MGM from bankruptcy - in much the same way Cinderella had for Disney in the previous year.

The story of the top-grossing movie of 1951 begins before the second world war and it involves Il Duce. The Italian dictator, Benito Mussolini, at the height of his powers, offered MGM $75,000 for the rights to Quo Vadis in 1938. Europe’s first fascist leader saw himself as an Italian studio mogul, like the giants of the American industry. He proposed a European Hollywood - to be built on farmland to the south west of Rome. His vision included updating the great 19th Century Italian operas for the age of the cinematic epic, on the soundstages of this new studio, Cinecittà - a suitably Wagnerian goal for an absolute ruler, I think you’ll agree. This investment in the cinema, the 20th Century’s first new mass medium, in the 1930s still in its first phase of explosive change, connected directly with the self-conscious modernity of Italian fascism (and of its aesthetic twin futurism). It dazzled many, especially the opportunists and megalomaniacs in the Hollywood system.

Hal Roach, swashbuckling Hollywood pro from the early years, the man who brought us Laurel and Hardy, and an opportunist if there ever was one, made a couple of attempts at a joint venture with il Duce. Their business would have been called R.A.M. - the Roach and Mussolini Company (did I tell you this stuff would make your head spin?). Roach claimed that the Italian state had committed $5M and that he’d keep 50% of the profits. A 12-film slate was drawn up, including four operatic epics - the first would have been Rigoletto. Roach was ultimately shamed into dropping the project in 1938 but not before he’d brought the dictator’s son Vittorio - playboy and film producer manqué - to New York. Vittorio stayed at the Ritz in Manhattan until he was finally chased from the country - in disguise and under an assumed name.

Had Quo Vadis been made back then - in the mid-thirties, before Cinecittà existed and half-way back to the beginnings of cinema - the cast might have included Hollywood’s highest-paid actor Wallace Beery as Nero and Marlene Dietrich as scheming empress Poppaea. Another attempt, which stalled in 1943, might have brought together Charles Laughton and Lana Turner in these roles.

When it finally began in 1948, the production was so huge that it became a critical element of the reconstruction of the Italian movie industry and also of the wider economy, still in ruins after the war. Giulio Andreotti, Christian Democrat Prime Minister in seven Italian governments between 1972 and 1992, said that Quo Vadis ‘did more for Italy than the Marshall Plan’. As a young Undersecretary for Entertainment (Sottosegretario allo Spettacolo) Andreotti became instrumental in rebuilding the industry, clearing the way for the reconstruction of Cinecittà (it had been used to accommodate refugees and camp survivors and it’s claimed some were still living there during production).

Il Divo

In Italian cinema he’s remembered as the man who brought the festival back to Venice, held the Americans in check by boosting Italian production and cooperated with the Vatican. The church hierarchy had been interested in the movies since the thirties (Pope Pius XI wrote an encyclical about the cinema in 1936) and after the war the cardinals cooked up the concept of ‘Catholic realism’ as a counter to the corrosive humanism of the neorealists. The Vatican wanted a strong, Catholic renaissance at Cinecittà and not the febrile, cosmopolitanism they feared the new generation of artists would bring them. Andreotti was happy to oblige. his 1949 censorship law (the ‘legge Andreotti’) was essentially an Italian Hays code, tying production loans and patronage to conformity with strict rules of morality. Divorce, sex and adultery were out but so was realism about crime and poverty - the law and the cinema it imagined was a carefully crafted counter to the angry spasm of neorealism. The reactionary elite could see that neorealism was more than a genre, that it might become a movement, a template for a new culture. And this could not be allowed.

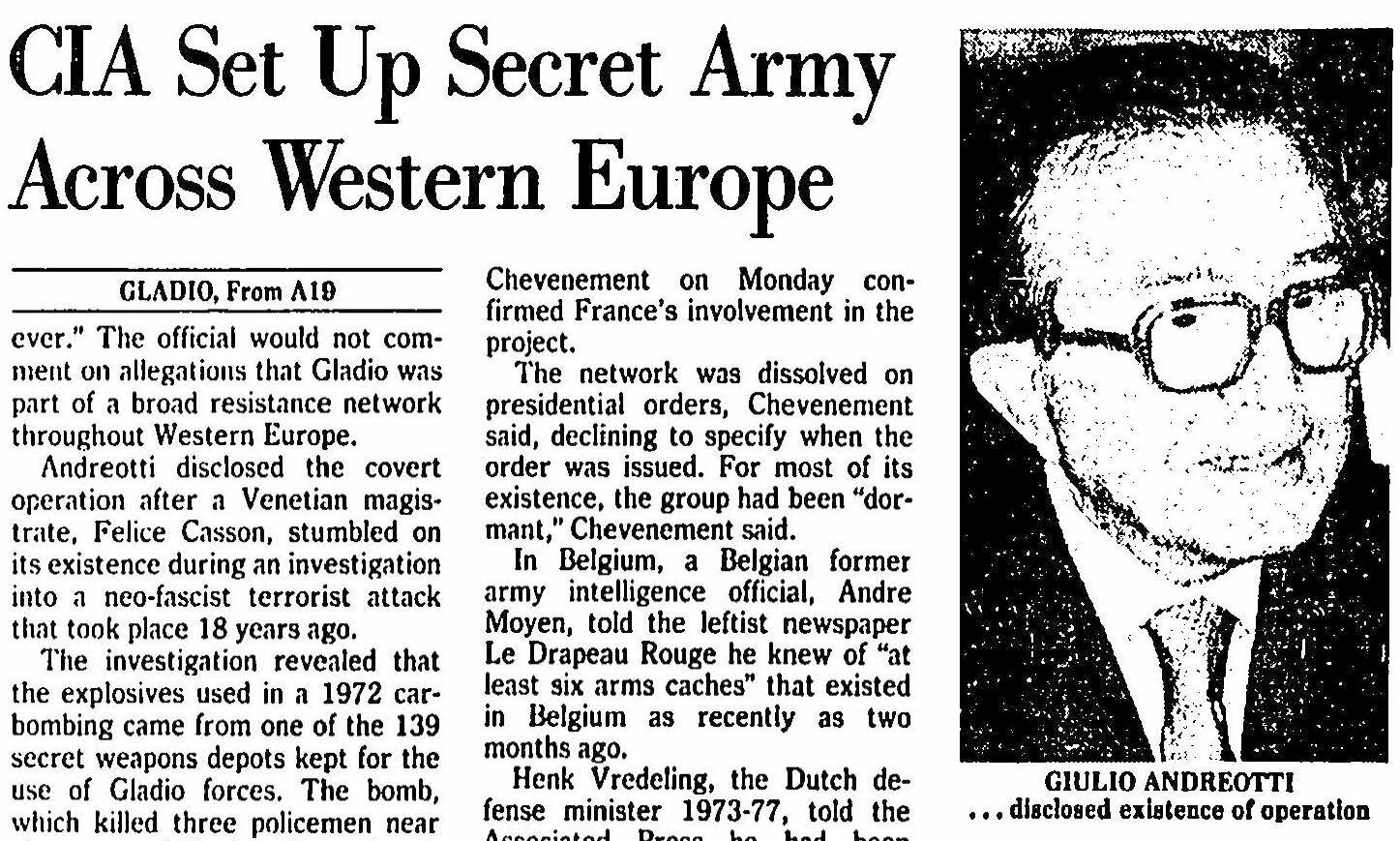

Andreotti was a member of Europe’s bloodless Christian Democratic elite - from the generation that - with all that American money - built a modern, conservative alternative to fascism, brutally flushed the democratic left out of European life and - not incidentally - began work on what would become the claustrophic EU regime. It’s hard to find a parallel for Andreotti in our politics. He was in or close to power for fifty years and took an interest in every aspect of the culture. He was close to the papacy and the mafia and the business elite and the spooks and generals of the North Atlantic alliance. He was no Mussolini but his outsize influence on cinema in Italy in the post-war period is comparable.

Money and violence

What are we learning here? What does Andreotti’s interference in the industry and his scheming to keep Italy in the American orbit tell us? Italy wasn’t special. The country may have been more vulnerable, more open to influence, than the other European nations after the war, but no part of Europe escaped the operation of the American state, American capital and the compliant North Atlantic consensus. The movies, as they began to dominate European markets, brought with them the values we’ve been learning about here - the individual, the market, the family and so on - but they also implanted a complete economic framework, a concrete set of production relations and the infrastructure of capital that sustained them. Markets for labour, finance, distribution and all the services the industry needed arose, on the Hollywood model.

And after the war, as the interconnectedness of the Atlantic economies increased, European men and women were organised into working patterns imported from California, investment and accounting methods were adopted, supply chains extended. Hollywood’s infiltration of the European imaginary in this period mirrored the secretive activities of the American-run ‘stay-behind’ operations, the organised - and violent - penetration of police, military and administration (the Italian operation was called ‘Operation Gladio' - Andreotti was involved, of course). The studios heroically advanced the cause of freedom and the individual while the spooks and gunmen held back the Commies.

Runaways

Making American movies abroad was not new but after the war it exploded. Quo Vadis was what the trades called a ‘runaway movie’ (the name for the whole category of foreign-made American movies). The economics was unarguable. Labour in poor Italy could be had for a fraction of the cost at home (this is the Rome depicted in Bicycle Thieves, remember). Production skills and talent were plentiful - and they’d worked right through the second world war in Mussolini’s propaganda and entertainment machine so their skills were fresh. Supplies of every kind, including lions, horses and bulls - all crucial to this production - could be had for rock bottom prices in bankrupt Europe. Production unions were hardly present.

European governments enthusiastically innovated - inventing much of the contemporary incentive regime for movie production in Europe - the tax breaks and subsidies and visa schemes that keep the studios coming now. Between 1949 and 1957 thirty Hollywood films were made in Italy (over a hundred in Britain in the same period - production money was spread around Europe). The effect was big enough to be felt in Los Angeles, where crews were out of work. The movies had become one of the first truly global businesses, dominated from Los Angeles but present in every advanced economy - capital, labour and ideas flowing with fewer inhibitions, pushing at the legal and constitutional limits, redefining the world economy.

And the movie?

The novel on which Quo Vadis was based was by Polish Nobel Prize-winner Henryk Sienkiewicz. I have not read this book (life’s definitely too short) but it’s still in print. By all accounts it’s a piece of work - a huge, Catholic pulp-epic from an author who specialised in pulp-epics. We’ll consider the movie in the next post.

Quo Vadis is on Amazon Prime and there’s a Blu-Ray.

A lot of the history here comes from this splendid book chapter by historical film expert Jonathan Stubbs.

There have been several adaptations of Quo Vadis for the screen, including a famous Italian proto-epic from 1913 (which, you’ll remember, is the year the GROSS project began) that also included lots of actual lions (and a Nero who looks spookily like Peter Ustinov).

I think of Wallace Beery as the Baldwin brothers rolled into one man - boorish, clever, funny, charming.

Opera is somehow always at the centre of media innovation.

There’s a 2009 Andreotti biopic called Il Divo. It’s on Amazon Prime.